A Statistical Analysis of "Hamptonese"

He worked for 14 years, literally turning trash into treasure.

Introduction

James Hampton is the creator of The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations’ Millennium General Assembly, a collection of 180 pieces of “outsider art” that currently reside at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington D.C.

A man of humble means, Hampton maintained a day job as a janitor. As an “outsider artist” he used the materials available to him: garbage. He worked for 14 years, literally turning trash into treasure, the above masterpiece.

As his wiki page explains:

Hampton built a complex work of religious art […] with various scavenged materials such as aluminum and gold foil, old furniture, pieces of cardboard, light bulbs, jelly jars, shards of mirror and desk blotters held together with tacks, glue, pins and tape.

Although historians have labelled Hampton an “outsider artist”, a more appropriate label might be prophet.

Hampton described his work as a monument to Jesus in Washington. It was made based on several religious visions that prompted him to prepare for Christ’s return to earth. Hampton wrote that God visited him often, that Moses appeared to him in 1931, the Virgin Mary in 1946, and Adam on the day of President Truman’s inauguration in 1949.

Want more background? Check out the video that inspired this article on YouTube.

But what does any of this have to do with statistics?

Stamp explains:

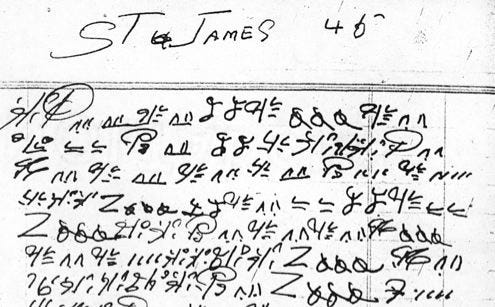

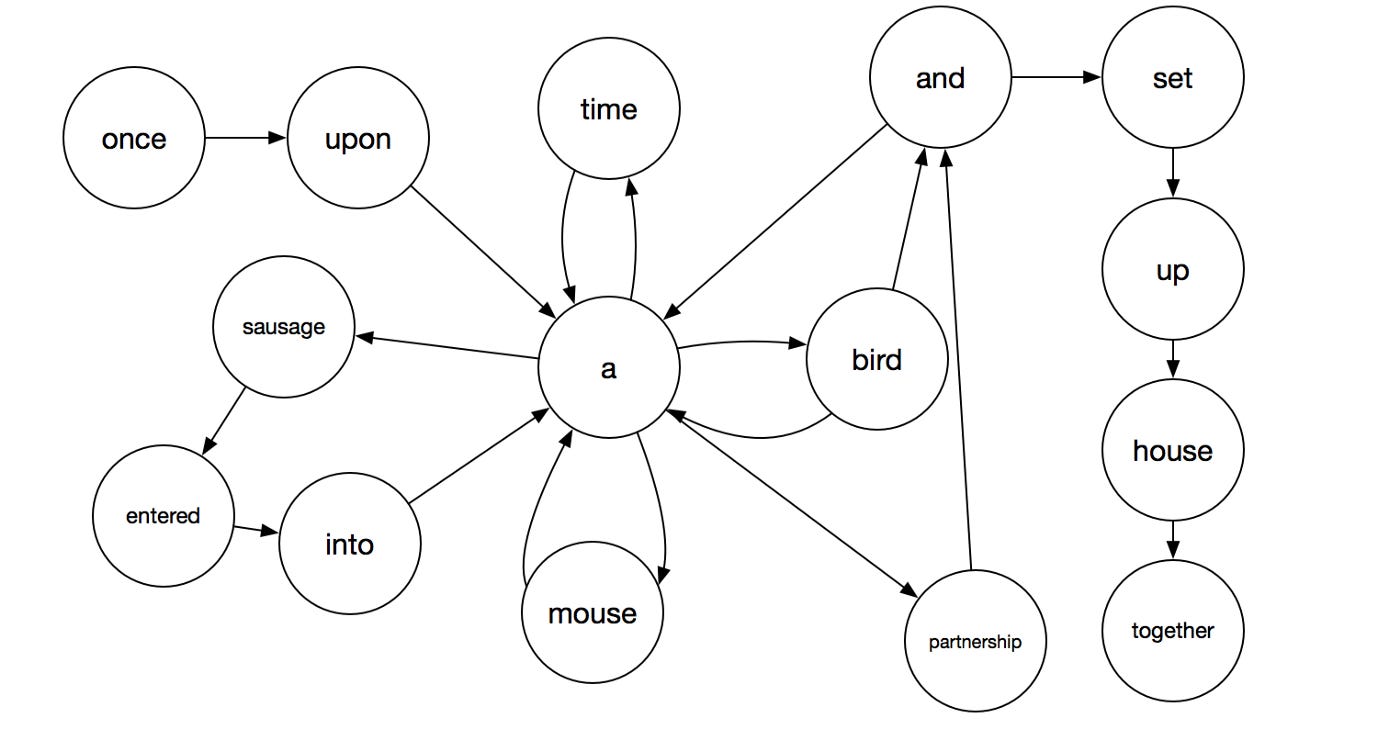

Hampton also left behind a notebook filled with more than 100 pages written in a mysterious script. This script has been dubbed “Hamptonese”. A partial page is pictured below.

Mark Stamp is the author of Hamptonese and Hidden Markov Models. Stamp, assisted by Ethan Le, went through the painstaking process of transcribing the notebook pages left by Hampton in an attempt to unlock their secrets.

Stamp writes:

This analysis shows that Hamptonese is not a simple substitution for English and provides some evidence that Hamptonese may be the written equivalent of “speaking in tongues”.

But statistics is all about the mathematics of extremely unlikely events. What if Hampton really was a prophet? What if “Hamptonese” really does contain divine revelations from some higher power?

If nothing else, this should be a fun excuse to work out our critical thinking and data science muscles.

Nerd note: The Python and R used for the following analysis can be found on github and I encourage those of you who can to check my work and let me know if you find any errors.

Sanity-Checking the Hamptonese Data

Let me begin with a huge “thank you” to Mark Stamp, and especially Ethan Le, for all their prior work on this subject. My initial goal was to replicate “Table 1. Hamptonese frequency counts” which is found on page 5 of Stamp’s paper.

Despite my best efforts, I was not able to replicate Stamp’s work exactly.

Some Hamptonese tokens are simply unreadable, and marked (*). Others are uncertain, and prefaced with (#). Furthermore, Stamp’s frequency table contains only 42 distinct Hamptonese tokens. This excludes tokens found in the official key (including “d2” and “J2”) and also excludes tokens found in the raw text transcript (including “Y1” and “P3”).

I eventually settled on two different methods for Hamptonese analysis.

Method A: I used everything provided in the raw text transcript and included uncertain tokens (#).

Method B: I started with the same raw text transcript but excluded uncertain tokens (replaced with *). I also ignored any tokens that do not appear in Stamp’s frequency table (replaced with *).

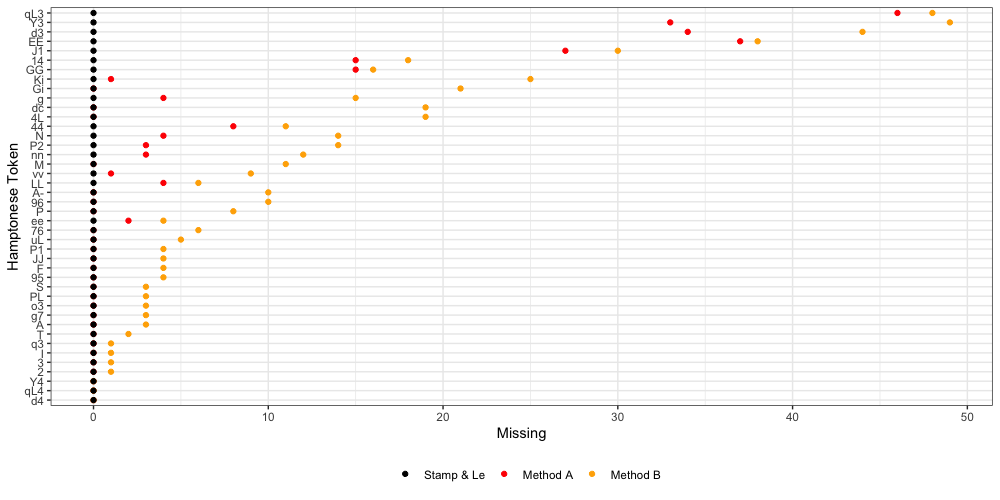

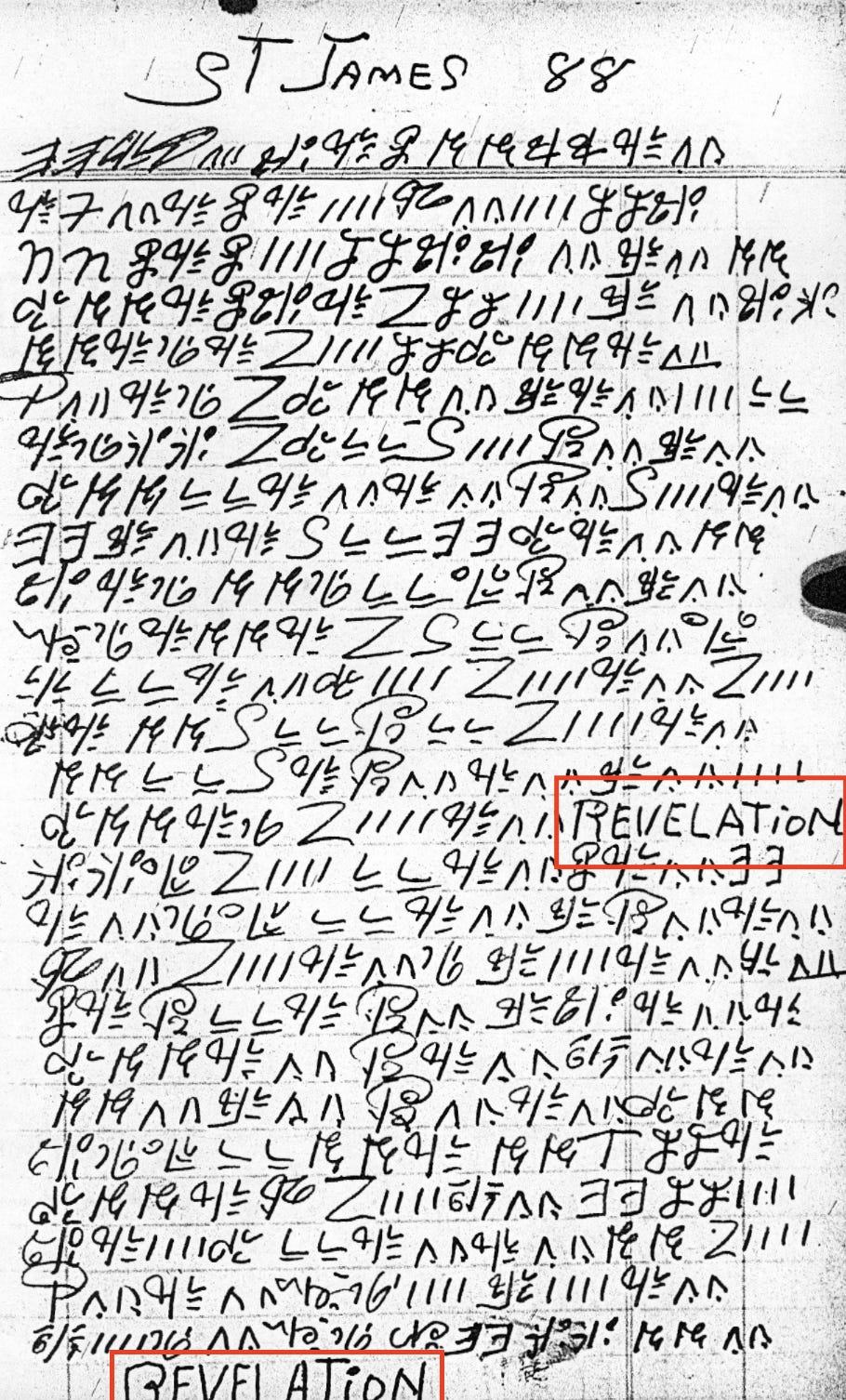

As we can see in the below table, neither method matches the exact counts or ranks of Stamp’s frequency table. These disagreements in rank show that these differences are not insignificant. We proceed having acknowledged this.

Table: Hamptonese Character Distributions

The above table also includes the tokens found in Method A that were excluded from Stamp’s table. This includes a few tokens we can recognize as names in English, such as “John”, “Jesus” and “St. James”.

Below we see error per distinct token:

Compared to Stamp’s frequency table, we find Method A is missing a total of 237 tokens, but also includes 256 tokens omitted by Stamp. In comparison, Method B is missing 499 tokens (ignoring uncertain items). This is out of a total corpus of roughly 29,000 tokens (~1.7%).

Zipf’s Law

Let us assume for a moment that Hamptonese is a form of natural language.

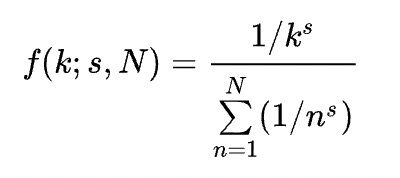

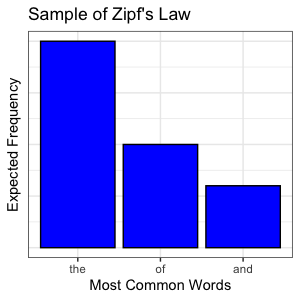

Zipf’s Law states that:

given some corpus of natural language utterances, the frequency of any word is inversely proportional to its rank in the frequency table.

Mathematically speaking, we can “tune” a Zipfian distribution to specific data by adjusting the exponent (s) to find the best fit.

The simplest case of Zipf’s Law is a “1/f” function. Given a set of Zipfian distributed frequencies, sorted from most common to least common, the nth most common frequency will occur 1/n as often as the first.

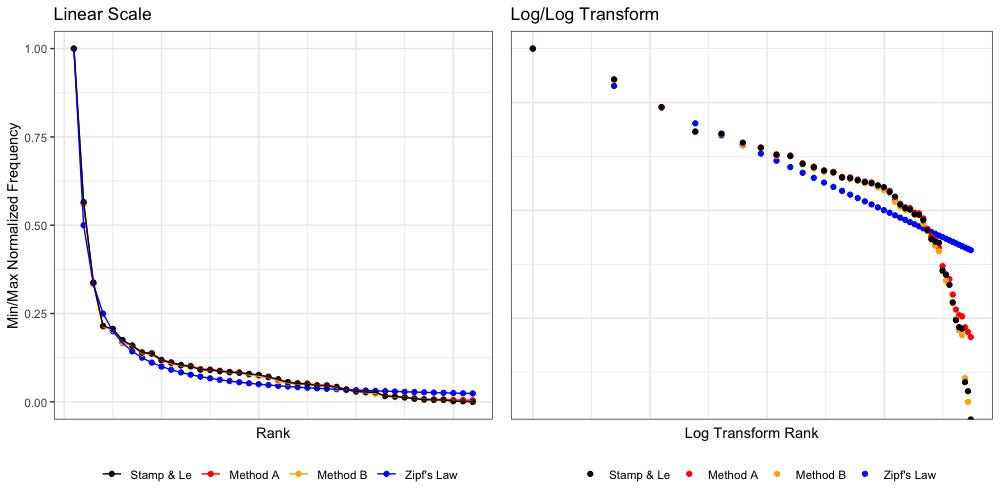

To help visualize Zipf’s Law, consider the following plot:

Below we have plotted Zipf’s Law (blue, 1/n, “untuned”) against the data according to Stamp’s paper and our own Method A and Method B.

The above plot tells us some interesting things. To better visualize we will break the right plot (log transformed) in half:

Hamptonese appears to be fairly Zipfian, but only if we restrict our view to the 32 most common tokens. Past that, everything falls apart. We also find that as we approach rarer tokens (left to right) our own Method A and Method B disagree more, with both Stamp and each other.

Assuming the right tail is the result of dirty data, it is quite possible that (with some tuning) we may find Hamptonese could pass a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and be formally proven as Zipfian. The temptation to ignore the right tail is considerable.

However, even if Hamptonese were formally proven to be Zipfian, this would not prove Hamptonese is a form of natural language, nor would it prove that Hamptonese could be translated into English.

From wiki:

[Zipf’s Law] occurs in many other rankings of human-created systems, such as […] ranks of notes in music, corporation sizes, income rankings, [and the] number of people watching the same TV channel.

It is important to remember that all sorts of things have Zipfian distributions, not just languages.

The Book of Nonsense

Statistics usually relies on comparison in order to make sense of things. What can we compare to Hamptonese?

There is a chance (however unlikely) that Hamptonese contains divine revelations from a higher power. The same can be said of the “Book of Psalms” from the King James Bible. And lucky for us, the good people at Project Gutenburg have already provided a full transcription.

There is also a chance that Hamptonese is pure nonsense, something that “looks and feels” like language, but has no actual meaning. To that end, I am proud to introduce The Book of Nonsense.

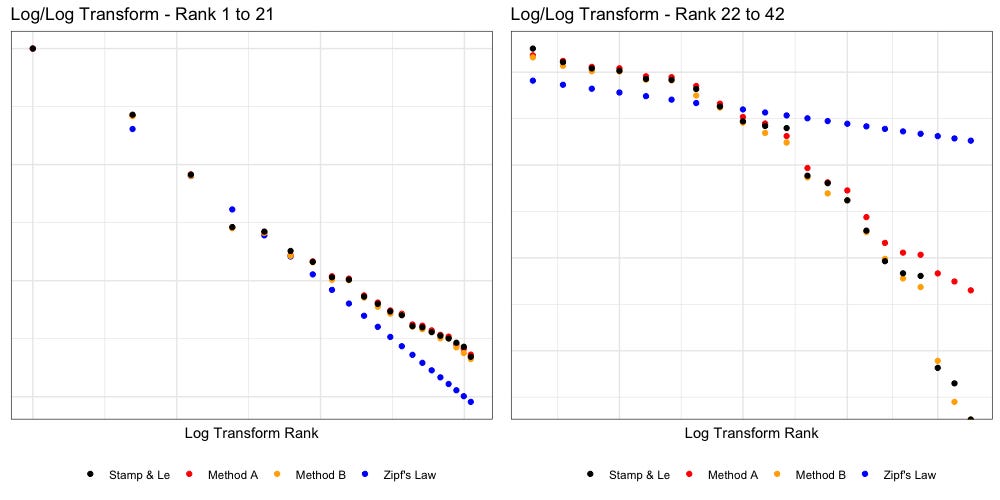

Using the “Book of Psalms” as our training corpus, we built a simple Markov Chain to generate something that “looks and feels” like divine revelation, but is actually total nonsense. We generated the same number of “books” with the same number of lines, each with the same number of words, using the starting word in each line as our seed. The next word in each “chain” is simply based on the probability of a given word following another.

Here are some random examples. All text has been converted to lowercase; all punctuation has been removed.

Psalms 23:1

the lord is my shepherd i shall not want

Compare to:

Nonsense 23:1

the eye is exceeding joy and glorious honour have

Another:

Psalms 91:1

he that dwelleth in the secret place of the most high shall abide under the shadow of the almighty

Compare to:

Nonsense 91:1

he forsook the cherubims let me and terrible to slay such knowledge in this be in wisdom made the

A final example:

Psalms 27:1

the lord is my light and my salvation whom shall i fear the lord is the strength of my life of whom shall i be afraid

Compare to:

Nonsense 27:1

the provocation thy greatness and jacob sojourned god didst hide thy law yea than the foundations be greatly moved at midnight of you more oppress spirit

Whether you are a skeptic, or a would-be disciple, you are welcome to skim the Book of Nonsense for yourself. At a glance, it has the “look and feel” of holy scripture, but on closer inspection, we find text that lacks any coherent meaning at all.

Tokenization

There are 150 books in both the “Book of Psalms” and “Book of Nonsense”, each of which contain multiple lines. Likewise we have 102 “Revelations of St. James” in Hamptonese, each of which also contains multiple lines.

In the first draft of this research we tokenized so that n-grams only included tokens on their own line. For “Psalms” this makes sense, as each line is a complete thought. But is the same true of Hamptonese? Do line breaks in Hamptonese represent anything significant? We cannot know for sure.

What we do know for sure is that James Hampton marked the end of each revelation with the word “REVELATION” in plain English. Normally James wrote one revelation per page, but in two cases (on p158 and p166) he wrote two on the same page.

In order to keep everything as “apples-to-apples” as possible, we re-ran the analysis, tokenized per-revelation, and per-psalm (and per-nonsense).

We find 102 “Revelations of St. James”, the shortest of which contains 120 symbols, and the longest of which contains 358, with an average of 289.6.

We find 150 books in the “Book of Psalms”, the shortest of which contains 33 words (163 characters), and the longest of which contains 2,423 words (12,264 characters), with an average of 284.6 words (1,410.8 characters).

We find 150 books in the “Book of Nonsense”, the shortest of which contains 33 words (173 characters), and the longest of which contains 2,423 words (13,200 characters), with an average of 284.6 words (1,549.2 characters).

Shanon’s Entropy and Conditional Entropy

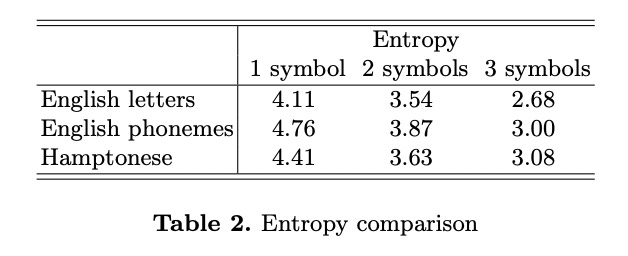

On page 6 of his paper, Stamp uses Shanon’s Entropy and Conditional Entropy to measure the information contained in Hamptonese compared to English.

Stamp writes:

The results in Table 2 indicate that for strings of three symbols or less, the information contained in Hamptonese is comparable to that of English. Of course, this does not prove that Hamptonese is a language, but it does suggest that it is reasonable to pursue the analysis further. [emphasis added]

To better understand what these entropy numbers mean, let us consider a specific example. Analyzing the “Book of Psalms”, given the string of [i]:

Table: Entropy Explained with Book of Psalms

In the “Book of Psalms” there are 179 different words that follow the word [i], with an average probability of 0.56%. When we start with only one word we have lots of uncertainty, high entropy.

However, things change as our string grows. For example, looking at the first 5 words, we find there are only 3 different Psalms that contain the string [i cried unto the lord]:

Psalms 3:4

[i cried unto the lord] with my voice and he heard me out of his holy hill selah

And:

Psalms 120:1

in my distress [i cried unto the lord] and he heard me

And:

Psalms 142:1

[i cried unto the lord] with my voice unto the lord did i make my supplication

We see 2 cases where the next word is “with” (66% probability) and 1 case where the next word is “and” (33% probability). Now we have fewer choices with higher probabilities; this means less chaos, more order, lower entropy.

Note that once we reach the string [i cried unto the lord with my voice] we lose certainty again (entropy goes back up) because the next word might be “and” (Psalms 3:4) or it might be “unto” (Psalms 142:1).

We can use this same methodology to tokenize on words (as above), or specific letters, or even on Hamptonese symbols:

Table: Entropy Explained with Hamptonese

Again we see that as the string grows longer, the uncertainty of what follows decreases, as does our entropy.

If we increased the string length to infinity we would expect conditional entropy to decay to zero. Once our strings include the entirety of each Psalm, (or each “Nonsense”, or each “Hamptonese Revelation”) no uncertainty will remain, since each item will have been “sorted” into its own perfect category.

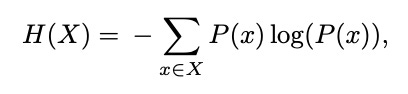

For strings of length 1 we will use Shannon’s Entropy:

For strings of length 2+we will use Conditional Entropy:

Stamp explains his methodology as follows:

the logarithm is to the base 2, and 0 log(0) is taken to be 0 […] We have also computed the entropy for two and three consecutive symbols using the conditional entropy formula. For example, the term associated with the string [abc] is given by P(abc) log(P(c|ab))

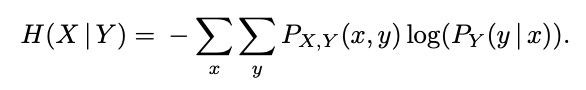

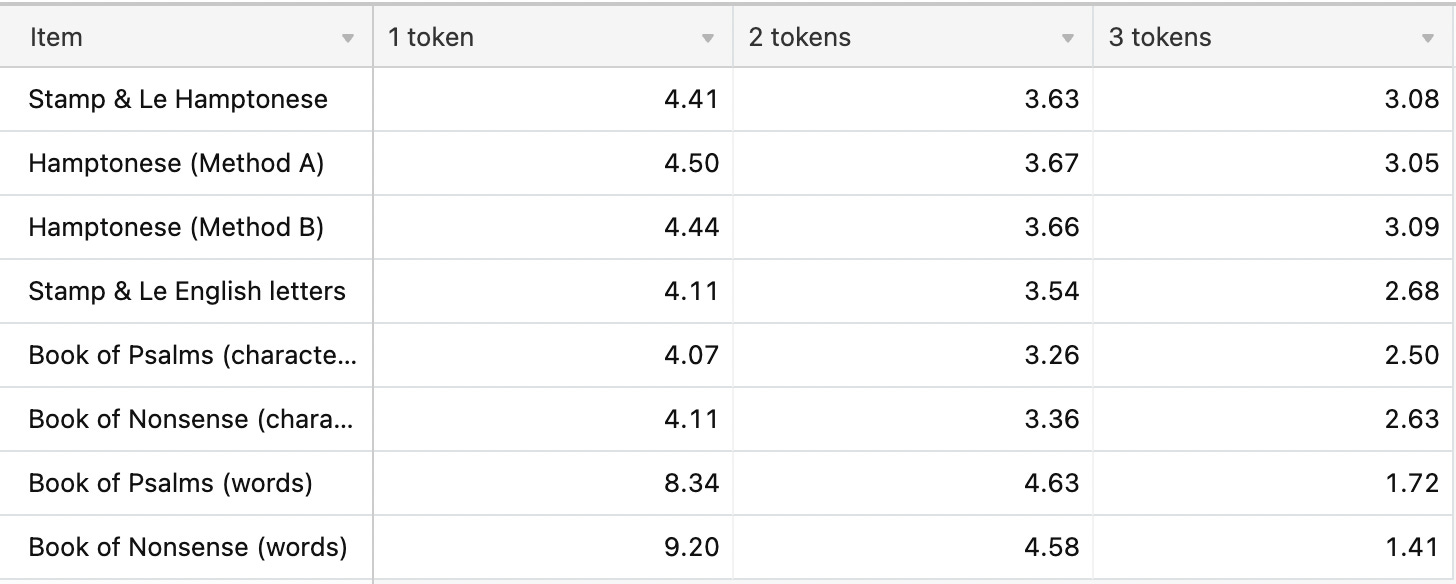

Our strategy will be to follow Stamp’s lead, and compare the difference in the decay of entropy in “Hamptonese”, versus the “Book of Psalms” and “Book of Nonsense”. We will follow Stamp’s methodology (above) in all of our entropy calculations. Hampton stopped with n=3. We will continue his work all the way through n=100. Ideally this will be large enough to find the points of minimum entropy for each of our token distributions.

Our Results

Here we compare our results to the results published by Stamp (pg 6):

Table: Full Results

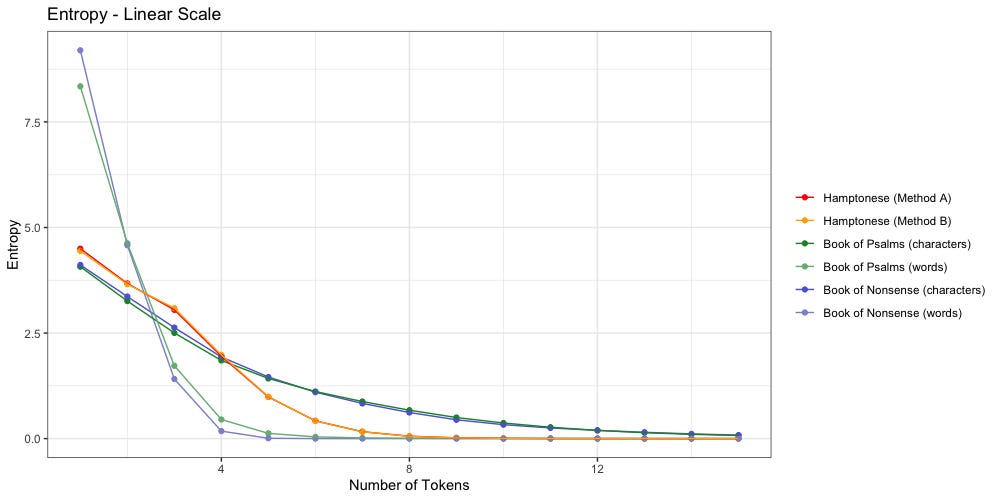

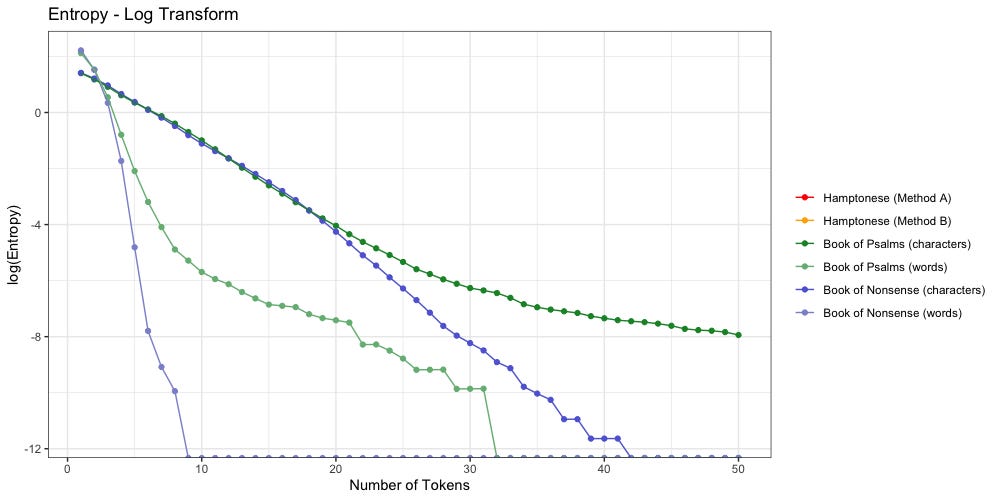

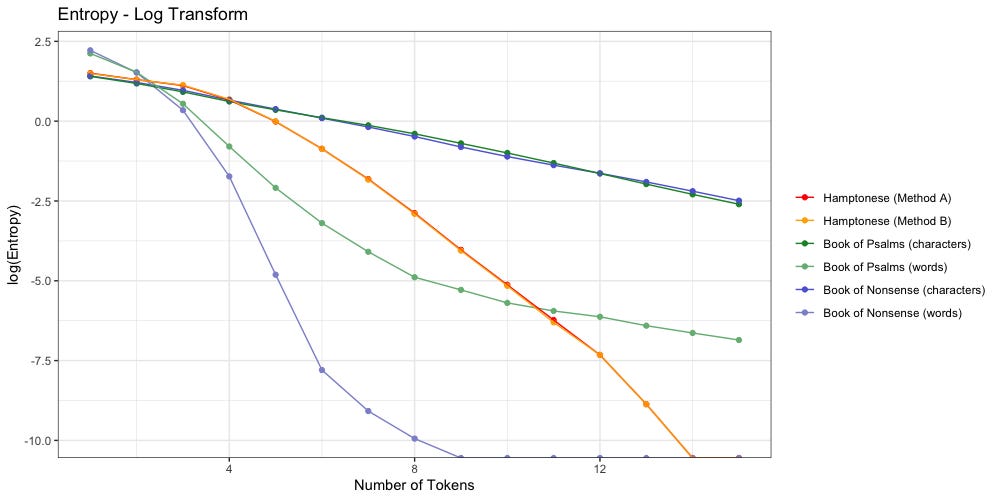

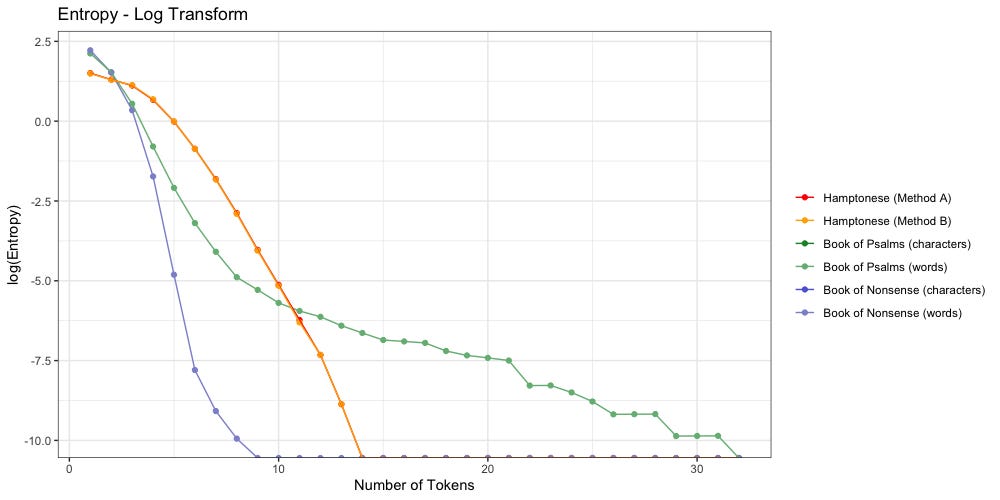

We have visualized the data below:

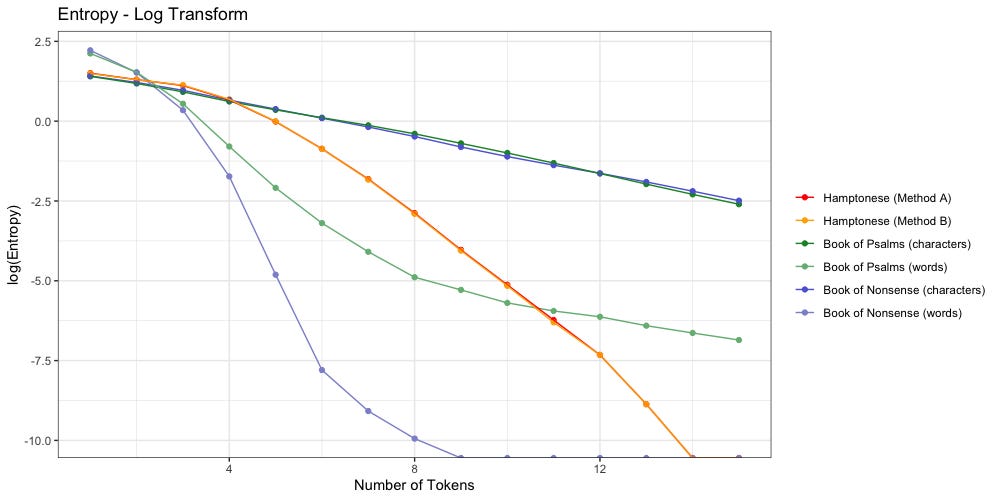

Below we log-transform the y-axis to more easily visualize things:

Questions, Answers, and Speculation

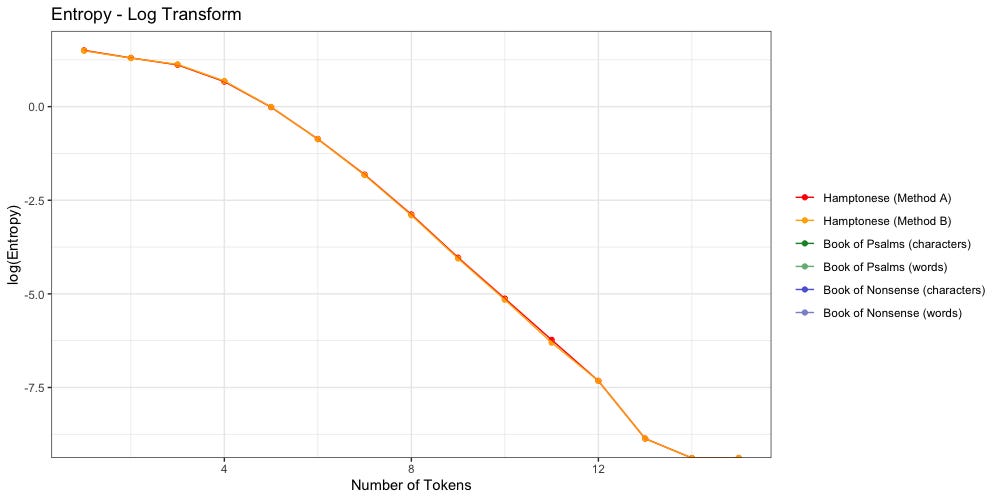

Are there any notable differences between Method A and Method B?

Nope.

Method A still “feels more right” to me, but for the sake of this entropy analysis, it didn’t make any noticeable difference. Method A and Method B agree: Hamptonese runs out of entropy after 13 characters.

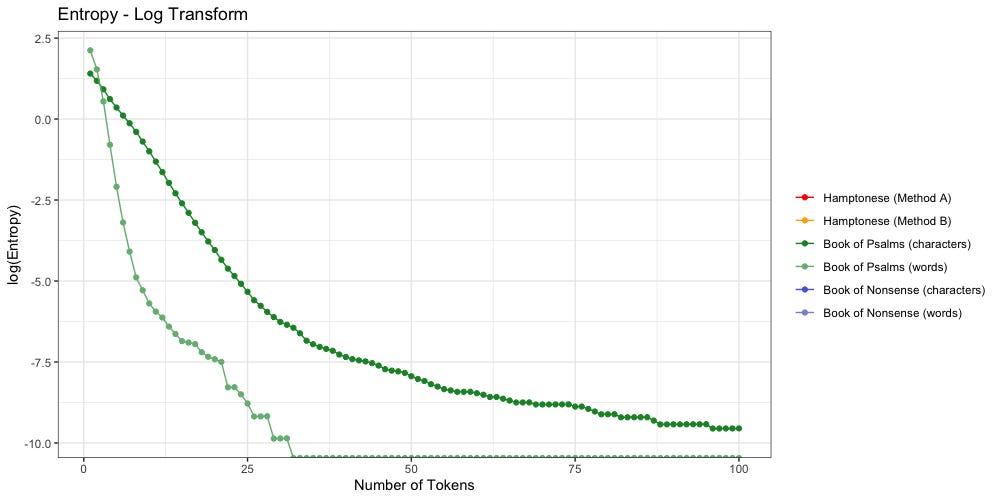

How does letter entopy differ from word entopy?

Let us focus on the “Book of Psalms” for a moment:

The dark green shows character entropy. There are only 27 characters to pick from (a-z plus space) so entropy starts lower. It also decays much slower. Even when n=100, entropy remains above zero at 0.00007. Considering the average “Book of Psalms” is 1,410.8 characters long, we may have a while yet to go before we find the point of 0 entropy.

The light green shows word entropy. We have far more words than we do letters. There are 2,890 unique words in the “Book of Psalms”, which explains why entropy starts so much higher. It also decays much faster. We reach zero entropy once n≥32. For comparison, the average “Book of Psalms” contains 284.6 words; we reach zero entropy once at 11.24% of the average.

Are there any notable differences between the “Book of Psalms” and the “Book of Nonsense”?

Yep.

Despite their identical shapes, we see that “Nonsense” decays much faster than “Psalms”. When tokenized by word, “Nonsense” reaches zero entropy once n≥9 (3.16% of average length). When tokenized by character, “Nonsense” reaches zero entropy once n≥42 (2.7% of average length)

We can attribute this faster decay to the fact our Markov Chain lacks the creativity of a human author. Mathematically speaking, our Markov Chain can only output a finite number of results. The probabilities which govern it are limited by the pairs of words which appear in the parent corpus. Compare to a human writer, who is limited only by the number of words in the dictionary (or in the case of Hampton, the number of characters they choose to invent).

Are these Hamptonese symbols words or letters?

Do the symbols of Hamptonese represent full words (ideas)? Or are they simply an alternative alphabet from which different words can be written?

The above plot confirms Stamp’s findings: Hamptonese is not a simple substitution for English. Change in Hamptonese entropy (orange/red) looks nothing like the change in character entropy (dark blue, dark green) found in both “Nonsense” or “Psalms”. It is possible that Hamptonese would better match the character distribution of another language.

Does this mean Hamptonese symbols represent full words?

If they do, they look closer to “Nonsense” to me.

Hot take: these symbols are neither characters nor words, but rather most likely a variation on the African-derived tradition of spirit writing which is not “readable” in the classic western sense of the word. They just so happen to follow a semi-Zipfian distribution, as do many data, many of which have nothing to do with natural language at all.

Does this mean Hamptonese is meaningless?

Assuming for a moment that Hamptonese is in fact a form of “spirit writing”, this does not mean it is devoid of any meaning. That said, whatever literal meaning it contains remains beyond the reach of us mere mortals.

Was James Hampton a prophet? Was he a man suffering from an undiagnosed mental illness? Was he something else entirely? I don’t know.

This much I do know: I am not the first to find meaning in James Hampton’s work, nor will I be the last. After all, it has been 57 years since his death, and yet, here we are, still discussing this fascinating man.

Josh Pause is a cranky old man who hates social media. You can find him on LinkedIn instead. The code and data used for this article can be found here. Please get in touch if you find an error, or have an idea for a future collaboration.