Measuring "Intelligence" Objectively (II)

Part 2: In pursuit of a counter example.

Introduction

Prerequisite Reading:

We start with a question: is it possible to measure intelligence objectively?

In Part 1 of this series we discussed a potential “Universal Intelligence Test” based on the 2003 paper Information Theory Applied to Animal Communication Systems and Its Possible Application to SETI by Doyle, Hanser, Jenkins, and McCowan.

Unlike any existing IQ test, we are looking for a method by which to objectively measure the intelligence of a message. Regardless of the language used. Independent of the cultural and personal biases that tend to skew these sorts of things.

Here in Part 2 we are looking for a counter-example: a message that passes the “Universal Intelligence Test” despite objectively lacking intelligence. We will also test things a bit more rigorously, a bit more “apples-to-apples”.

Put simply: in this article our objective is to test our test.

Our Data

In order to take a better look at this proposed “Universal Intelligence Test” we analyzed the text of four classic books available via Project Gutenberg:

We also included the first half of the classic Don Quijote, in the original Spanish. For our control group, we turned to the Lorem Ipsum generator, which creates meaningless placeholder text.

This time we tokenized things a bit differently.

Imagine we are back at SETI, and we have just received a message which includes a sequence of exactly 100,000 symbols. This time we will make no assumptions about words versus characters, capitalization, punctuation, or anything else. We will simply take the first 100,000 symbols of each of these sources exactly as provided.

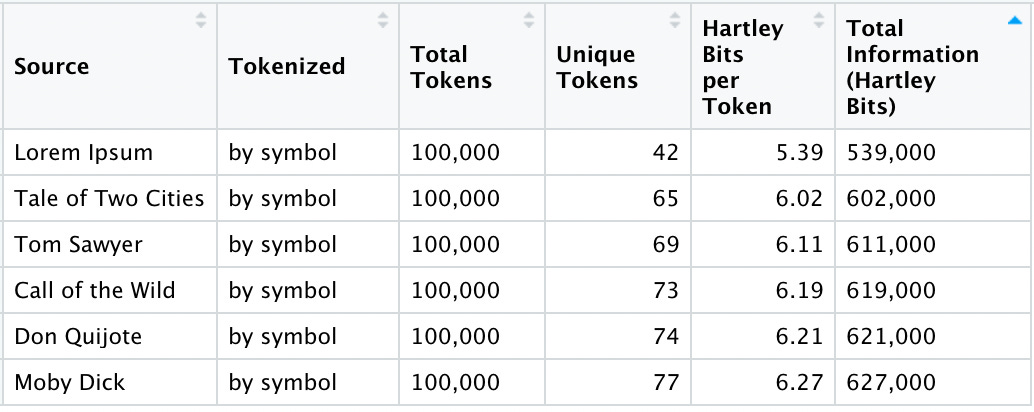

Here are our new summary stats:

Now that we are comparing “apples-to-apples” with the first 100,000 symbols from each source, we see that Total Information, as measured in Hartley Bits, depends entirely on the number of unique tokens in each corpus.

Condition #1: the Zipf slope

Recall our first condition for intelligence:

Has a Zipf slope approaching -1

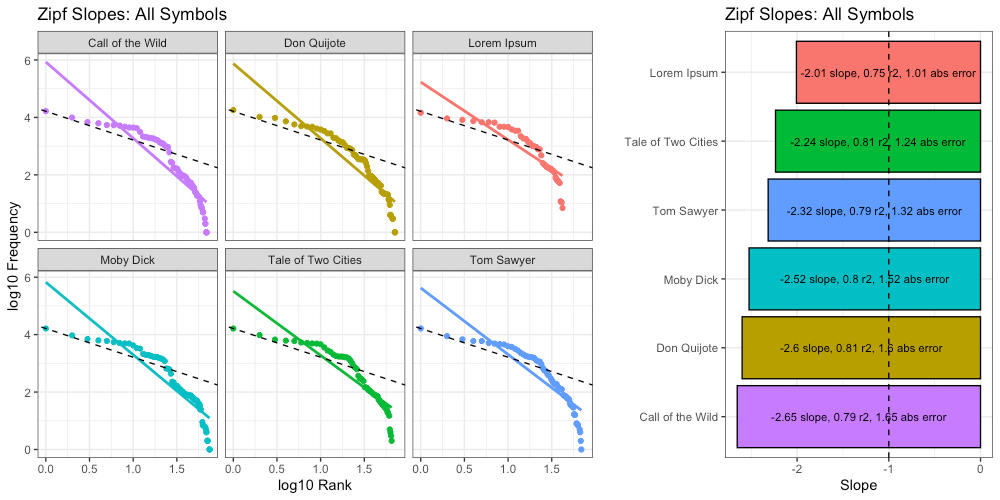

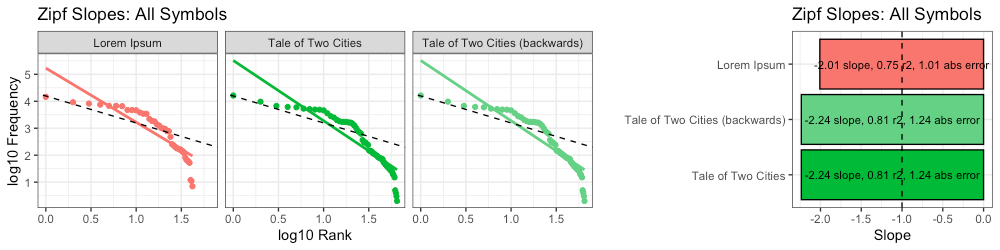

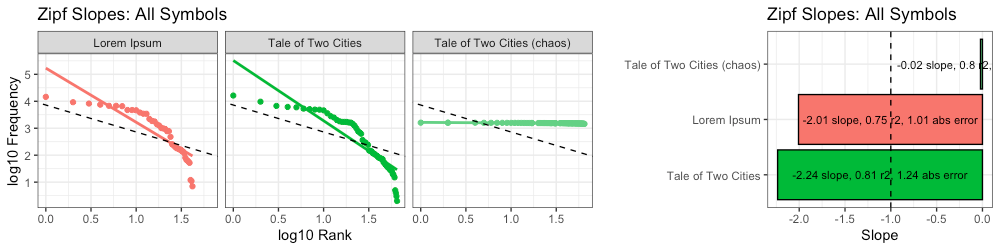

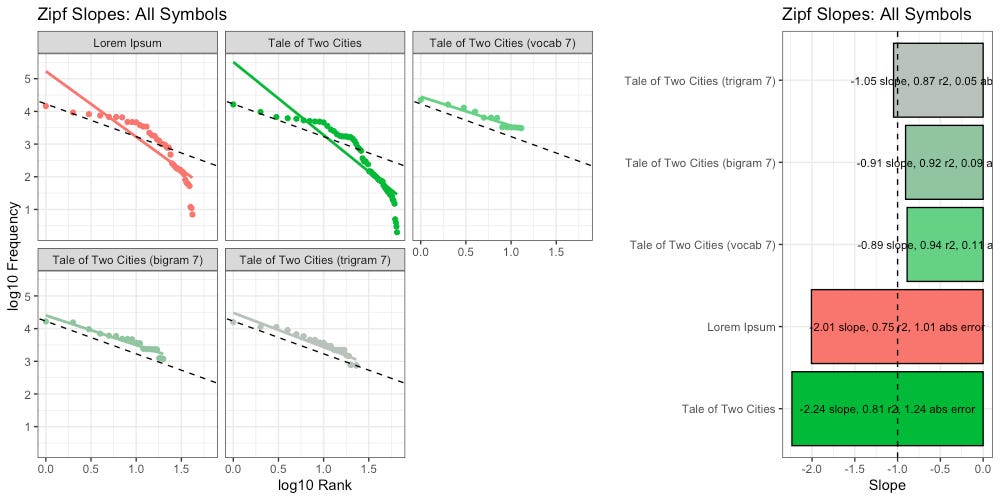

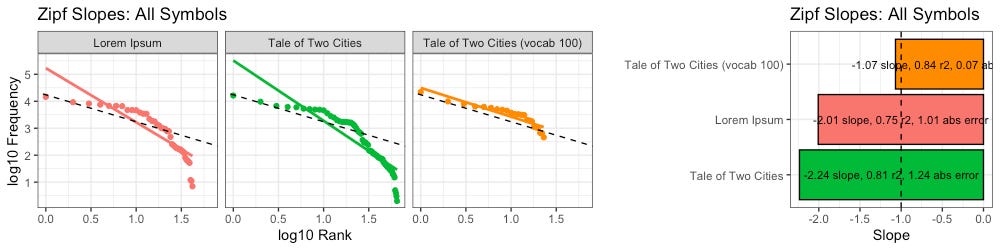

Here we calculate Zipf slopes using the same methodology from Part 1. Here are the results when we consider all 100,000 symbols, exactly as provided:

As before, our right-tails are messing up the “Zipfyness” of these distributions. Below we can see how these Zipf slopes change as we consider more symbols:

Below we rank all sources according to how close their Zipf slope is to -1. Those closest to -1 are on the top, and those furthest away are on the bottom. We see these ranks bounce around as we consider more and more symbols:

Based on Zipf slope alone, Lorem Ipsum is more-or-less indistinguishable from the other, intelligent, texts. We will need to take another look at higher-order entropy in order to see the difference.

Condition #2: higher-order entropy

Recall our second condition for intelligence:

Shows evidence of higher-order entropy

Here we calculate higher-order entropy using the same methodology from Part 1.

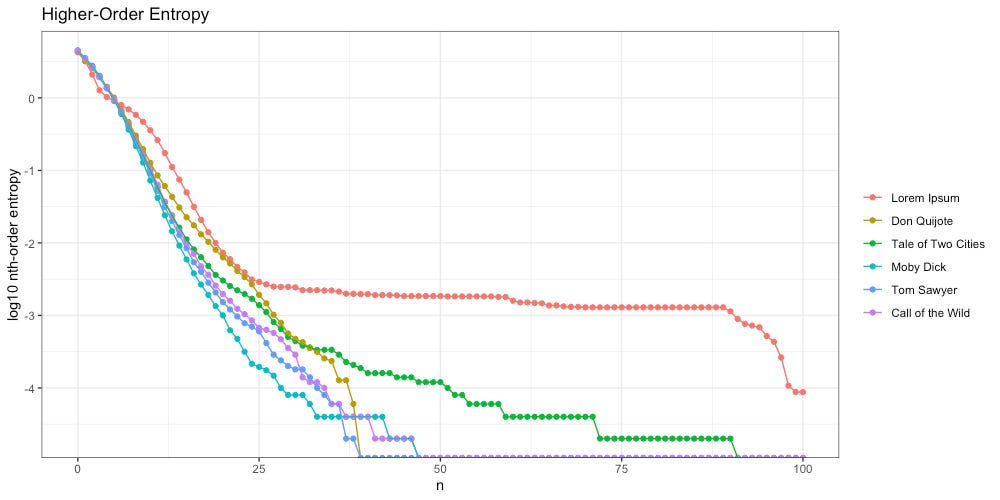

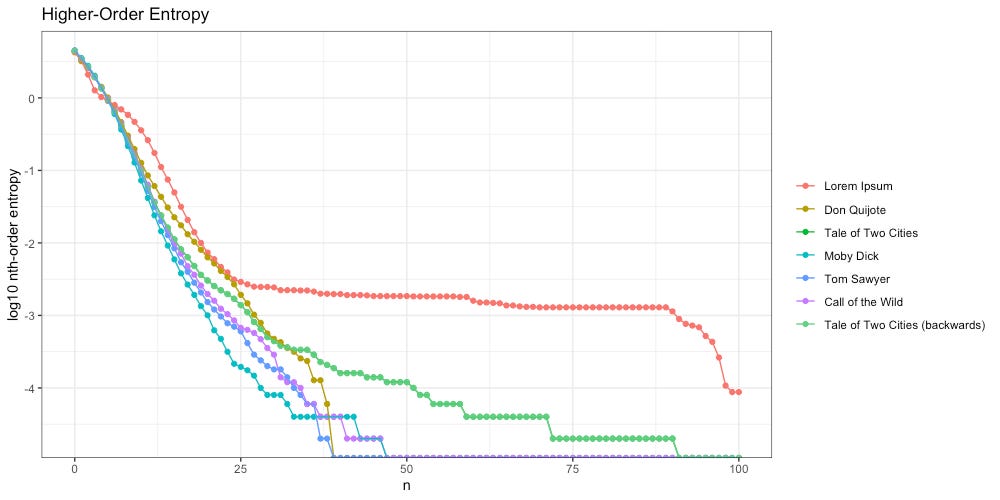

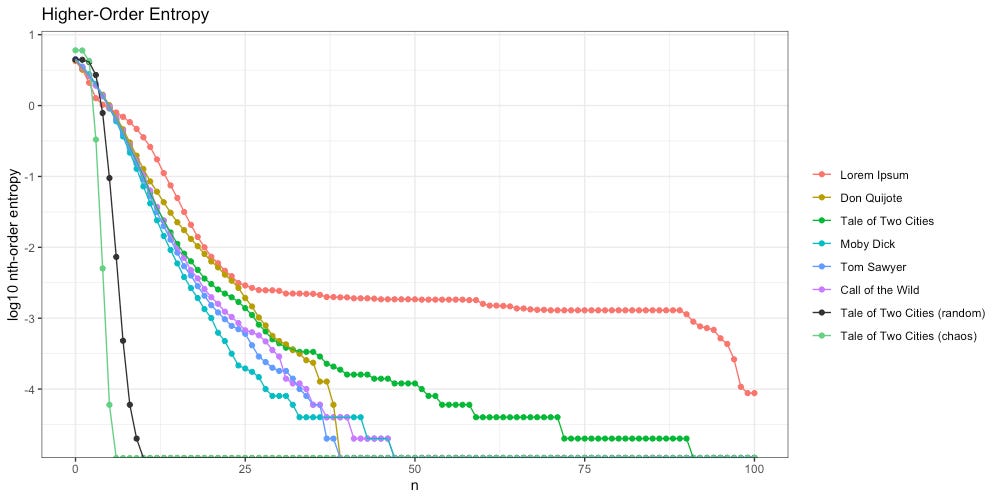

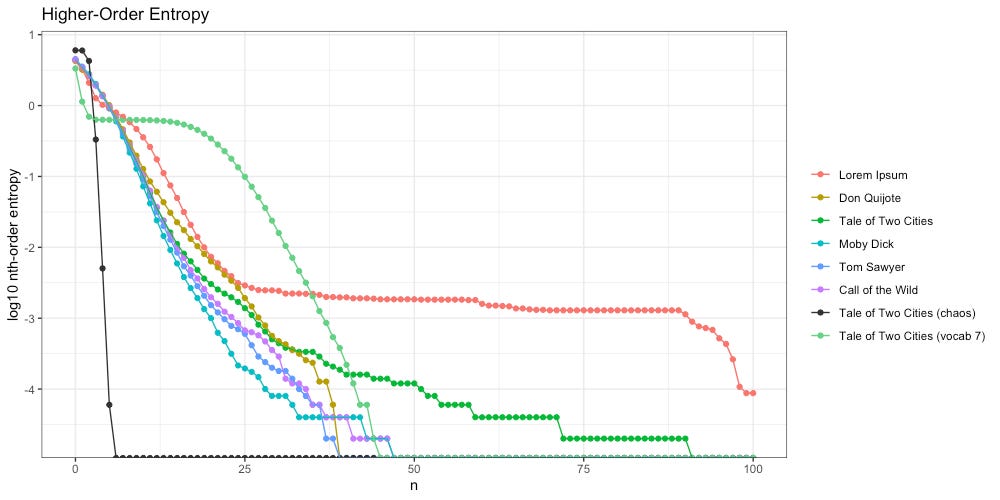

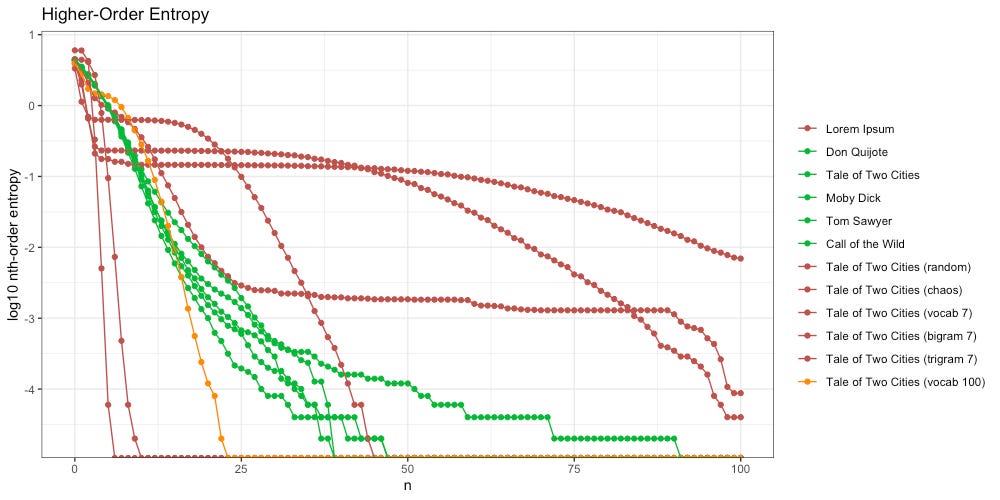

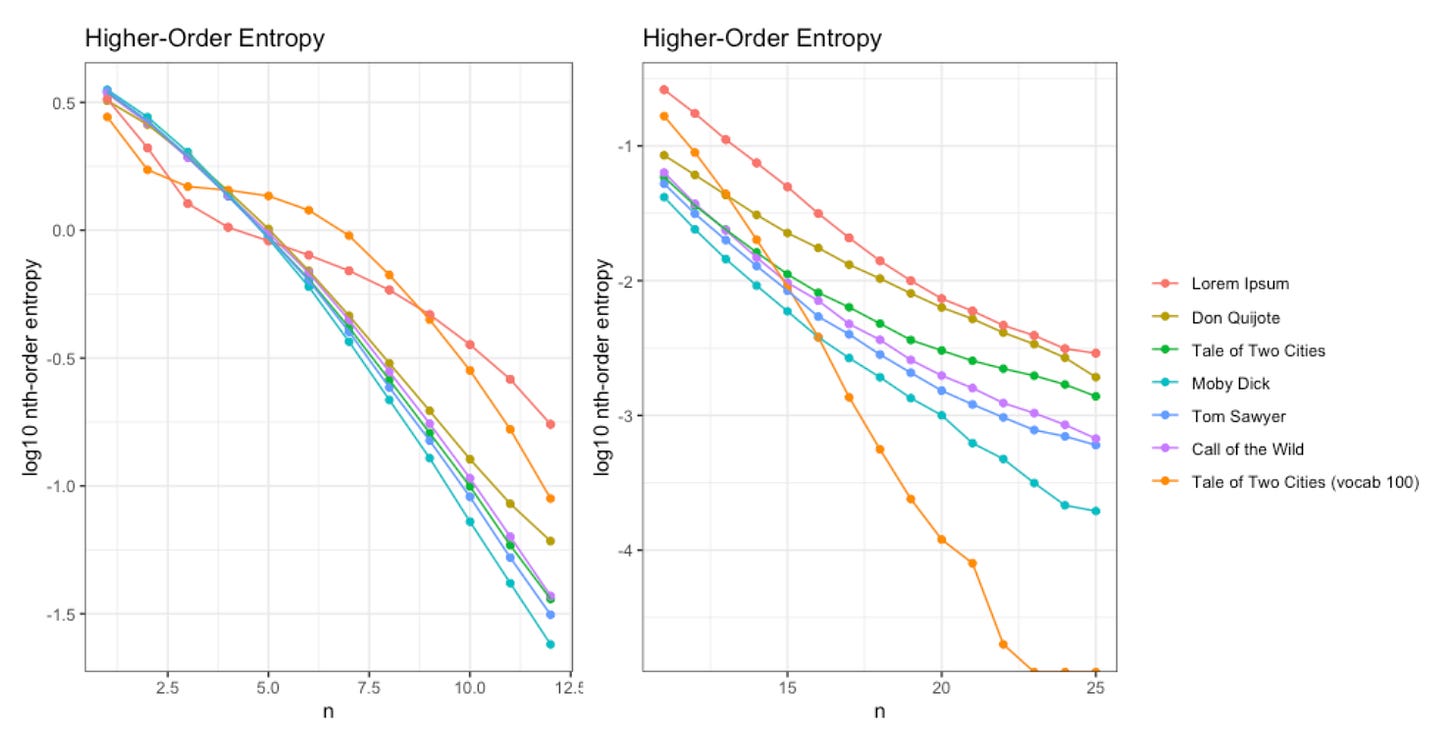

Once again we see Lorem Ipsum (red) behaves differently; unlike the intelligent texts, it “flattens out” around 25th-order entropy, and stays flat through the 90th.

We also notice A Tale of Two Cities (green) flattens out more than the other intelligent texts do. What is going on here? The culprit is a piece of repeated text, found in CHAPTER III. The Night Shadows:

“Buried how long?”

The answer was always the same: “Almost eighteen years.”

“You had abandoned all hope of being dug out?”

“Long ago.”

“You know that you are recalled to life?”

This passage is repeated a few times in this chapter, with slight alteration:

“Buried how long?”

“Almost eighteen years.”

“You had abandoned all hope of being dug out?”

“Long ago.”

The words were still in his hearing as just spoken…

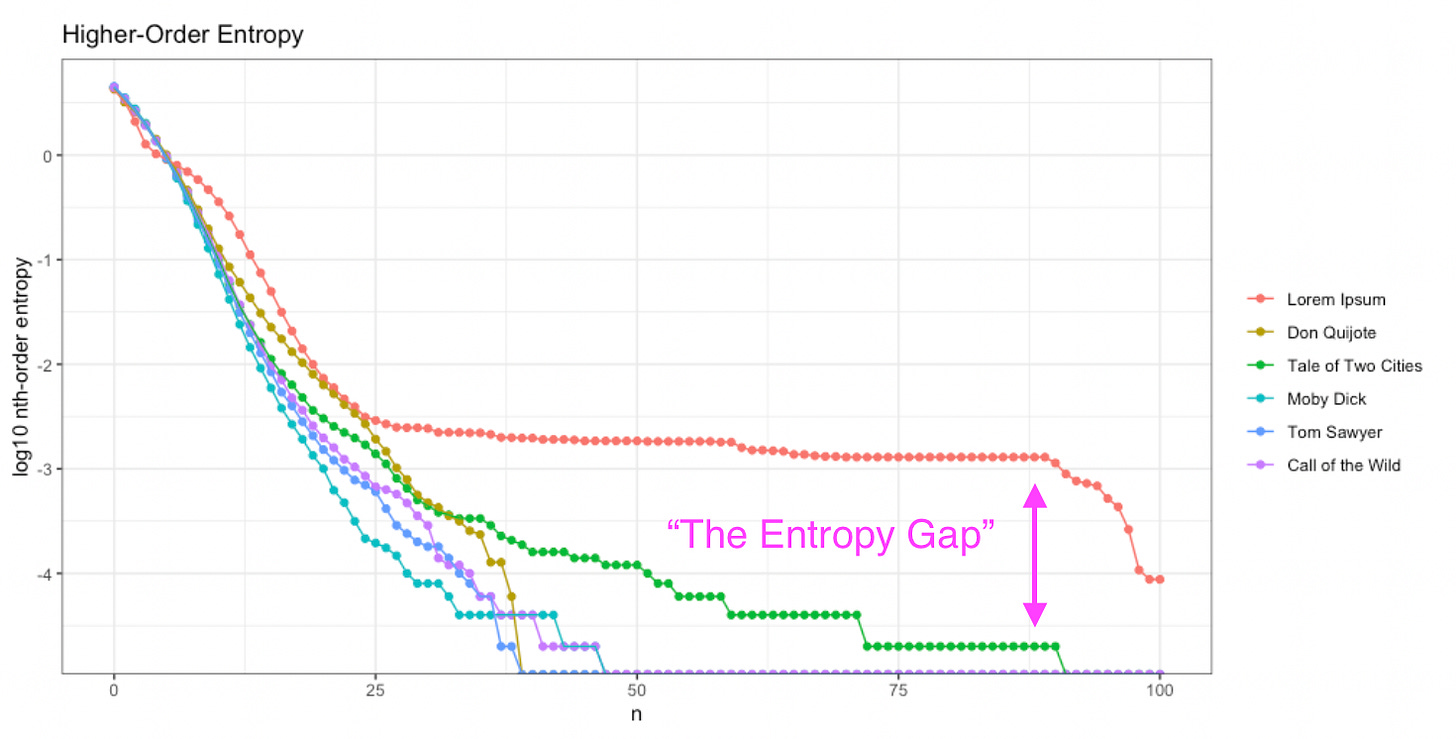

Despite this literary choice by Dickens, we can see “The Entropy Gap” between an unintelligent message (Lorem Ipsum, red) and an intelligent author intentionally repeating a passage (Tale of Two Cities, green):

In general terms, our “Universal Intelligence Test” passes another sanity check, without any NLP preprocessing required.

Now how can we break it?

Experiment #1: seitiC owT fo elaT A

What happens if we reverse the sequence of symbols?

For example, A Tale of Two Cities begins with the iconic:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,

After reversing the sequence, our new message ends with the notably less iconic:

,semit fo tsrow eht saw ti ,semit fo tseb eht saw tI

Because both messages contain the exact same symbols, with the exact same quantities of each symbol, their Zipf slopes are identical:

Interestingly, not only are Zipf slopes identical, higher-order entropy is too:

This time our flattened entropy slope (light green) is due to the repeated passage:

”.oga gnoL“

”?tuo gud gnieb fo epoh lla denodnaba dah uoY“

”.sraey neethgie tsomlA“

It would appear that our “Universal Intelligence Test” works just as well backwards as it does forwards. That might come in handy elsewhere.

Experiment #2: A Tale of Random Cities

What happens if we ignore the sequence of symbols?

As we know, A Tale of Two Cities begins with the iconic:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,

Now we keep all the same symbols, but randomize their sequence. The resulting message begins like so:

n h

es hanipbeenswtn

insol ”yn,cui rnn Waimtyidjb

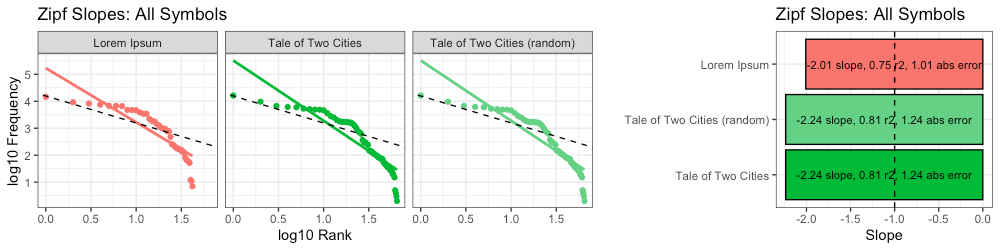

Once again, because both messages contain the exact same symbols, with the exact same quantities of each symbol, their Zipf slopes are identical:

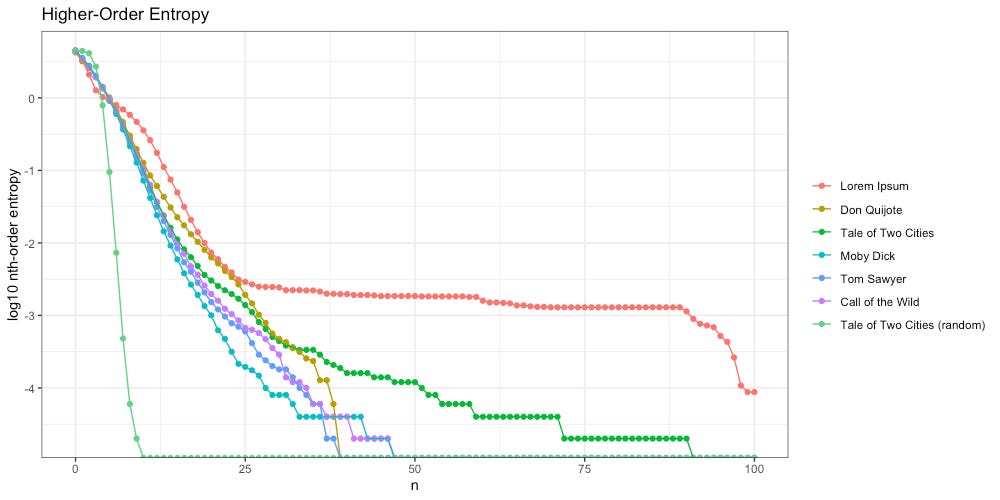

However, in terms of higher-order entropy, we see a stark difference:

When we randomize the sequence of symbols in the message, higher-order entropy crashes out at the 10th-order, far to the left of the intelligent texts. That makes intuitive sense, as our text is no longer intelligent.

Or is it?

Consider for a moment our potential “plumber’s friends” who live on the alien planet of Tralfamadore. They do not experience linear time the way us humans do.

Each clump of symbols is a brief, urgent message— describing a situation, a scene. We Tralfamadorians read them all at once, not one after another.

We can only hope our Tralfamadorian friends will dumb things down a bit for us, and be sure to maintain sequence in any messages they send our way.

More seriously: although our “Universal Intelligence Test” works just as well backwards as it does forwards, it is important to note that it remains wholly dependent on sequence. That is, we can read left-to-right, or we can read right-to-left, but we have to pick one or the other.

Experiment #3: A Tale of Total Chaos

What happens if we generate a chaotic message on purpose?

We find that our corpus of A Tale of Two Cities contains 65 unique tokens:

We will select 100,000 of these symbols at random, with replacement, with each symbol given an equal probability of selection.

As we know, A Tale of Two Cities begins with the iconic:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,

Our new message begins as follows (total chaos):

eOx“b‘ywWVm.YorfYxtK,JvcNUbOB-“pKN?bG”Y:(

Yt:WtnYHt

Because the distribution of symbols is no longer the same (each symbols in “chaos” has the same 1-in-65 probability) the Zipf slope is not even remotely “Zipfian”:

We also see a stark difference in terms of higher-order entropy:

With our “chaos” message, higher-order entropy crashes out at the 6th-order, even faster than “random” (10th-order). That makes intuitive sense, as our text now seems even less intelligent than before.

However, if intelligence is simply a measure of how quickly entropy reaches 0, that would mean Lorem Ipsum is the most intelligent. That can’t be right. There must be more to this story.

Experiment #4: The Lorem Ipsum Paradox, Test I

We know from Part1 that, when tokenized without punctuation, and transformed into lowercase, Lorem Ipsum contains 186 unique words. These words are not being placed in any intelligent sequence, however, the symbol distribution is dependent on those limited number of words.

Does this explain the Lorem Ipsum paradox we see above?

As we know, A Tale of Two Cities begins with the iconic:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,

Given a vocabulary of only 7 words:

"it","was","the","best","of","times","worst"

We will select 50,000 words at random, with replacement, with each word given an equal probability of selection. We will then compose a new message containing the first 100,000 symbols from our random word selection (with spaces added in between our selected words).

Our new message begins as follows:

of best was the best the times was was of of worst

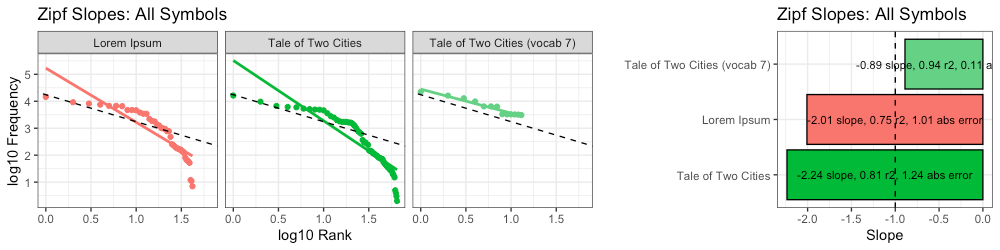

We find this new message, which is limited to a vocabulary of only 7 unique words, has a Zipf slope of -0.89, which is closer to the ideal slope (-1) than either Lorem Ipsum or the original A Tale of Two Cities:

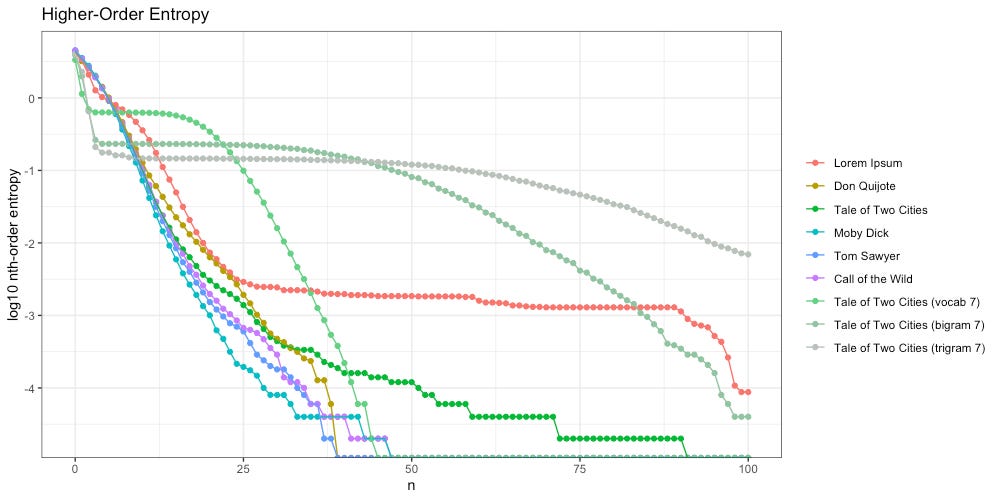

We can see the higher-order entropy of this new message below (light green):

Instead of decaying rapidly to the left of the intelligent texts (e.g. “chaos”), our new message flattens out a bit, like Lorem Ipsum does, before crashing to zero.

Can we find something even closer to Lorem Ipsum?

Experiment #5: The Lorem Ipsum Paradox, Test II

We tried repeating Experiment #4 with different numbers of unique words in the sample vocabulary, but this didn’t get us any closer to Lorem Ipsum. However, we eventually stumbled on another idea: word-based ngrams.

We repeated the methodology of Experiment #4, this time using bigrams instead.

Given a vocabulary of only 7 bigrams:

"it was","the best","of times","age wisdom","season darkness","everything before","direct heaven"

We generated a message that starts like this:

age wisdom everything before it was the best it was

We did the same given a vocabulary of only 7 trigrams:

"it was the", "best of times","worst times wisdom","age foolishness epoch","belief incredulity season","Light Darkness spring","hope winter despair"

Which generated a message that starts like this:

it was the worst times wisdom it was the hope winter despair

We found that as we increased the size of our ngrams, we got slightly closer to the ideal Zipf slope (-1):

We also found that as we increased the size of our ngrams, the decay of our higher-order entropy got flatter, and looked more like Lorem Ipsum:

This led us to an exciting observation.

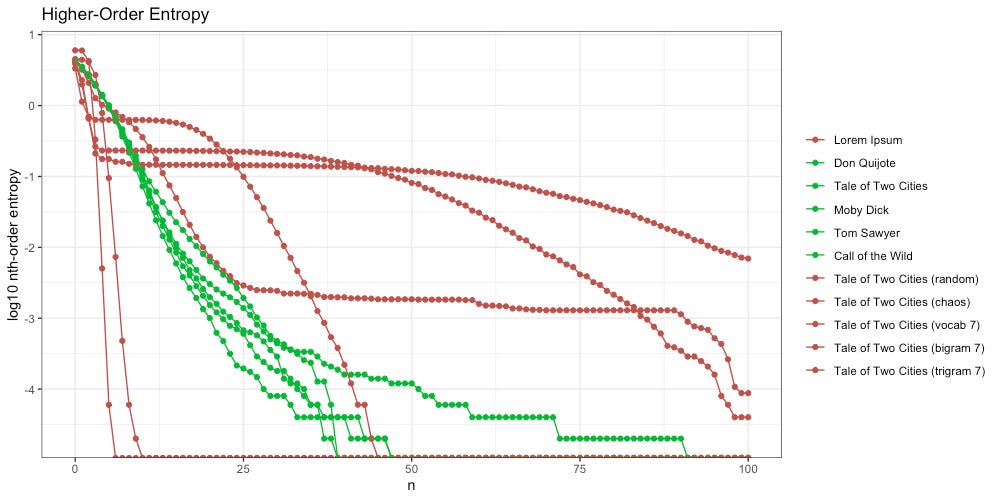

Observation #1: The Goldilocks Zone

The ideal entropy slope is neither too flat, nor too steep. It appears there exists a “Goldilocks Zone” between the extremes, and this is where we find intelligence.

Colors simplified for emphasis:

In red on the left we find Experiments #2 and #3. Here we are dealing with nothing more than a random sequence of symbols, indicating no intelligence at all.

In red on the right we find Experiments #4 and #5 plus Lorem Ipsum. Here we are dealing with a sequence of symbols that are logically organized into words, which is indicative of more intelligence.

However, the placement of these words is random and disorganized. To say it another way: smart enough to form words, but not smart enough to use them.

In the middle we find “The Goldilocks Zone”. Here we are dealing with a sequence of symbols that are logically organized into words, and furthermore, those words are further organized and used via some sort of intelligent grammar.

Observation #2: A Potential Counter Example

For comparison, the first 200 symbols in A Tale of Two Cities are as follows:

CHAPTER I.

The Period

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age ofwisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it

was the epoch of incredulity, it

We took the top 100 words from the cleaned, tokenized corpus of a A Tale of Two Cities. From these top 100 we randomly selected 50,000 words, with replacement, with each word given an equal probability of selection. We then composed a new message containing the first 100,000 symbols from our random word selection, with spaces added in between our selected words.

The first 200 symbols from that new message is follows:

one the upon me from am said miss them at for from by this good some to she be had as himself when her from were out looked that here your my down night not night my with with much have for defarge c

Let us agree this new message is not as intelligent as the original.

In terms of Zipf slopes, this new message (vocab 100) passes the first condition better than the intelligent text it was based on.

In terms of higher-order entropy, this new message (vocab 100) seems to slip right through the middle of “The Goldilocks Zone” described above:

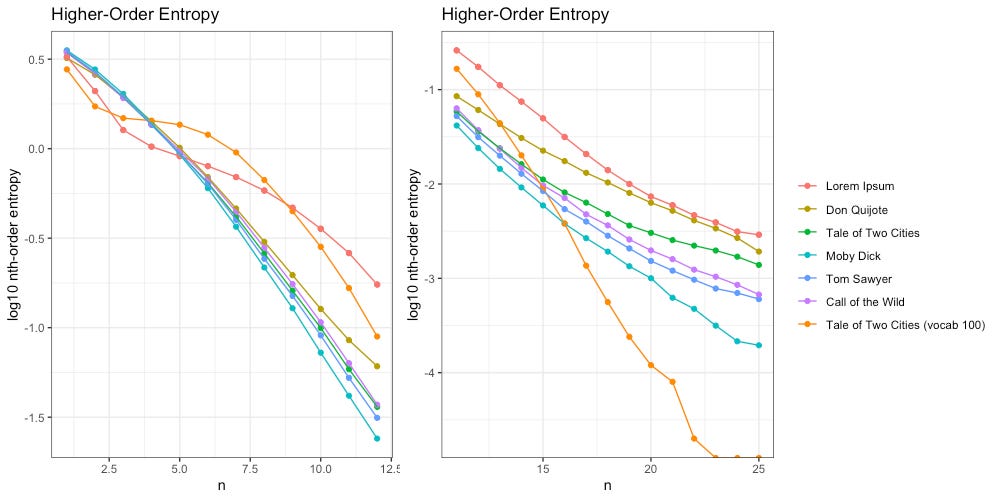

That said, when we zoom in, we see differences between this new message (vocab 100, orange) and our intelligent texts.

On the left (2nd-12th order entropy) we can see our new message clearly bulges a bit, as does Lorem Ipsum. On the right (10th-25th order entropy) we see the entropy decays much faster than our intelligent texts do.

This suggests that “The Goldilocks Zone” remains a viable postulate, but still requires a more rigorous definition.

Observation #3: A Flawed Point Estimate

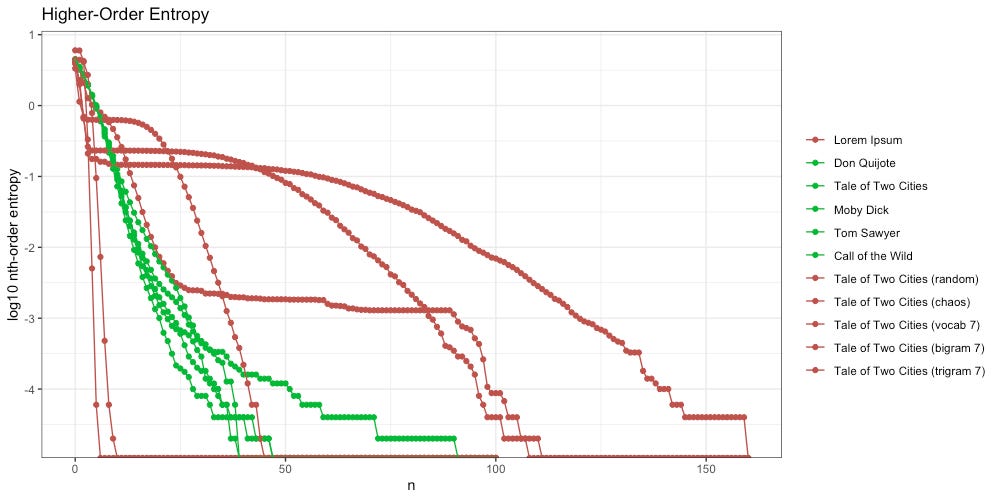

We find that once we reach the 160th-order, all of our messages have decayed to zero entropy. Since we cannot take the log of zero (undefined) they exist as negative infinity in the world of R, and flat at the bottom of the below plot:

In an ideal situation, we could reduce the above information into a single point estimate, a single number that could be used to determine (a) if a given message is intelligent and (b) rank intelligence accordingly.

To better illustrate what we want, let us simply consider the cumulative sum of the base-10 log of our nth-order entropy (ignoring zero). This has been animated in the plot below. We can see how rank changes as n increases.

At a minimum, we would want the above plot to group the green (intelligent) messages together. Sadly, the long tail of higher-order entropy found in A Tale of Two Cities messes that up. It seems to do at least pretty good with everything else.

Of course, in terms of comparing intelligence, the question still remains: is it better to be at the top of the list, or the bottom? That is still unclear.

Getting closer, but still a long way from home.

Questions, Answers, and Speculation

Have we found a counter example?

After taking a second look at these plots, I’m not so sure.

There is something clearly different about these intelligent texts. The bulges on the left, the slopes on the right… further investigation is warranted.

Can we further refine our “Universal Intelligence Test”?

I think we can, and I think variance holds the key.

Where do we go from here?

I’m heading back to the lab to test out a few more ideas.

Stay tuned.

Subscribe on substack so you don’t miss it.

Josh Pause is a cranky old man who isn’t pretty enough for Instagram. You can find him on LinkedIn or Substack instead. The code and data used for this article can be found here. Please get in touch if you find an error, or have an idea for a future collaboration.

Works Cited

Hamptonese and Hidden Markov Models, 2005, Hampton, Le

Information Theory Applied to Animal Communication Systems and Its Possible Application to SETI, 2002, Doyle, Hanser, Jenkins, McCowan

Using information theory to assess the diversity, complexity, and development of communicative repertoires, 2002, Doyle, Hanser, McCowan

Transmission of Information, 1928, Hartley