Measuring "Intelligence" Objectively (I)

Part 1: Can we design a truly universal intelligence test?

Introduction

Imagine you are working at SETI, scanning the night sky for radio signals from far away galaxies. You press your ear to the headphone, eyes closed, listening intently against the faint buzz of background radiation.

Now imagine you’ve just heard something strange.

Was that a broadcast from an intelligent alien civilization?

Was it just meaningless noise?

More importantly: how would you know the difference?

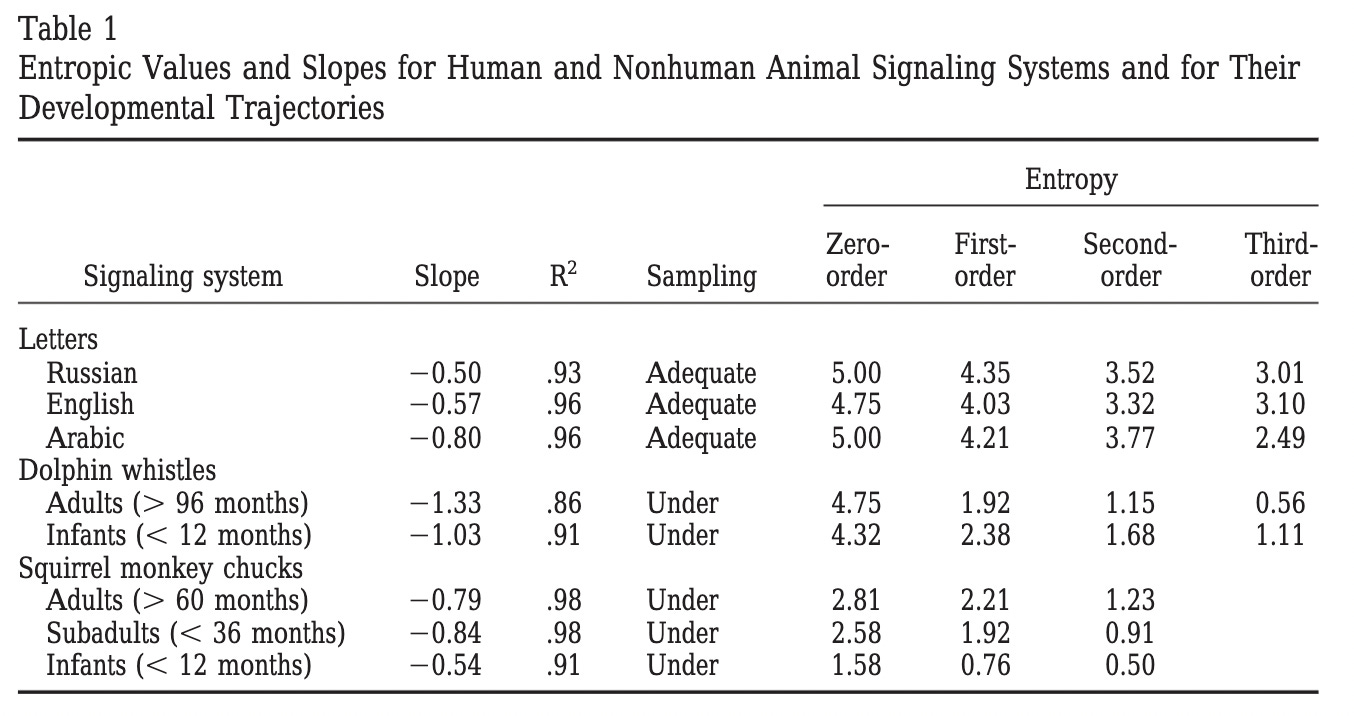

This is the question the authors were trying to answer in the 2003 paper Information Theory Applied to Animal Communication Systems and Its Possible Application to SETI by Doyle, Hanser, Jenkins, and McCowan. If the authors are correct, we may be able to identify intelligence with nothing more than a Zipf plot and a little higher-order entropy. Could it really be so simple?

According to McCowan, et all: we can observe specific patterns in distribution and entropy which appear to hold true regardless of language, or species. Whether speaking English, or Spanish, or Dolphin, the same universal signs of intelligent communication can be observed.

The authors suggest these observations might serve as the basis to test whether or not a given alien communication is intelligent.

Could they also be used to test whether the same is true of a given AI?

The Theory

It all boils down to Zipf slopes and higher-order entropy.

What are “Zipf slopes” and why do they matter?

From Information Theory […] and Its Possible Application to SETI:

A special case of Shannon first-order entropy […] sometimes known as Zipf’s principle of least effort. […] Plotting the logarithm, base-10, of the frequencies [counts of each token] against the [base-10] logarithm of their rank (1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc.) [Zipf] found that most of the dozens of languages he plotted in this way yielded a slope of -1 [negative one].

This plot has been extended to several non-human signaling systems including porpoises, chickadees, orcas, squirrel monkeys, and even the chemical signals of cotton plants.

Adult bottlenose dolphins show a Zipf slope of -0.95 […] while adult squirrel monkey chucks produce a Zipf slope of no greater than about -0.6, indicative of a less complex signaling system.

In other words, as we move closer to this optimal Zipf slope (-1) we find more evidence of intelligence, even when applied to non-humans.

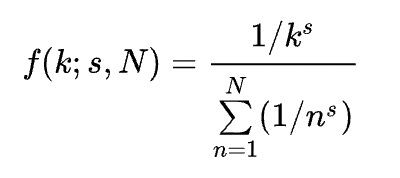

These Zipf slopes are more formally defined here: Using information theory to assess the diversity, complexity, and development of communicative repertoires.

Put simply: first we count up how many times each token (symbol, word, dolphin whistle, etc) appears in our corpus (data). Then we rank them (1, 2, 3, etc.) from most appearances to least, take the base-10 log of both numbers, and plot them. We then use linear regression to find the best-fit Zipf slope (aka the Zipf coefficient).

In addition to Zipf Slopes, these researchers also looked at higher-order entropy. [Ed. Note: We also looked at Zipf and higher-order entropy while replicating the work of Stamp & Le for this article on “Hamptonese”]

What is “higher-order entropy” and why should we care?

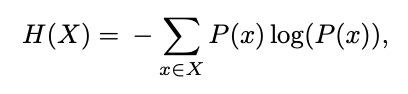

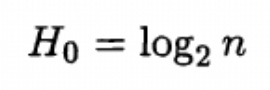

Entropy is simply a measure of uncertainty. Imagine I picked a book at random, turned to a random page, and selected a random word. If I asked you to guess which word I had picked, you would face a lot of uncertainty.

There are at least 470,000 unique words in English. Assuming they all have equal probability, it is extremely unlikely you would guess correctly. However, you could figure out which word I had picked through a series of 19 strategic “yes” or “no” questions. More specifically: by asking log2(470,000) questions (18.8423).

The process is simple: split the 470,000 potential words into two groups of 235,000 and ask if the word I selected is in Group A or B. Take the relevant group, and split it in half again, this time into two groups of 117,500. And again, into groups of 58,750. And again, into groups of 29,375. Since 29,375 doesn’t divide equally into two groups, you will need exactly 18.9423 questions to arrive at the final group, which will contain the random word I picked.

This is zero-order entropy, aka Hartley Bits; the heart of the digital revolution; the math that allowed us to reduce our entire world into a series of 1’s and 0’s.

But wait a moment- we know that the 470,000 words of English do not all have equal probability. For example, the word “the” appears more often than the word “disestablishmentarianism”. When trying to guess the random word I selected, it would be wise to keep that in mind. It would reduce your uncertainty a bit. This is an example of first-order entropy.

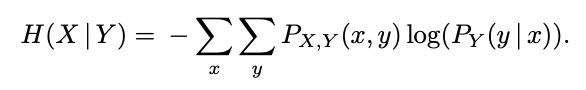

Now imagine I told you that the random word I selected was “peanut”. Imagine I asked you to guess the next word. You would still face uncertainty, but given a little context, you are now more likely to guess the next word correctly. This is an example of second-order entropy.

Now imagine I asked you to guess the next word that follows this string:

peanut butter and…

Are you immediately thinking of the word “jelly”?

If so, you already understand fourth-order entropy intuitively.

And so it goes, up through nth-order entropy, all the way to infinity (or more likely, you run out of words). Eventually each string gets sorted into its own “perfect group of one” and entropy reaches zero.

Mathematically speaking, the term associated with the input “peanut butter and jelly” is given by:

P(“peanut butter and jelly”) * log2[P(“jelly”|“peanut butter and”)]

Our total nth-order entropy is simply the sum of the above for all ngrams of length n-1 combined with all possible nth words that might follow (the log2 term).

This can be performed on any tokenization, allowing us to compare monkey chucks and dolphin whistles to letters or words in English… or Spanish… or even some mysterious communication from an alien civilization (or extremely advanced AI).

In their research, McCowan, et all, noted that the amount of uncertainty decreases as we look at higher-order entropy, and took this as evidence of intelligence in the communication of monkeys, dolphins and humans. Considering our “peanut butter and jelly” example above, it makes intuitive sense that any intelligent communication should follow this same pattern.

Mathematically speaking, we expect to find another negative slope here no matter what. Regardless of any intelligence, or lack thereof, as n approaches infinity, entropy approaches zero.

The question is: how might these slopes differ?

And what might that tell us about intelligence?

Our Experiment

In this experiment we will consider a “Universal Intelligence Test” based on the work by Doyle, Hanser, Jenkins, and McCowan.

IF a given communication:

Has a Zipf slope approaching -1

AND:

Shows evidence of higher-order entropy

Can we conclude it to be intelligent?

Our Data

In order to take a better look at this proposed “Universal Intelligence Test” we analyzed the text of four classic books available via Project Gutenberg:

Of course, our universal test won’t be very useful if it only handles English. To that end, we also included the first half of the classic Don Quijote, in the original Spanish, as provided by Project Gutenberg.

For our control group, we needed something without intelligence. For this we turned to the Lorem Ipsum generator, which creates meaningless placeholder text; a useful tool for designers, but lacking any intelligence.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

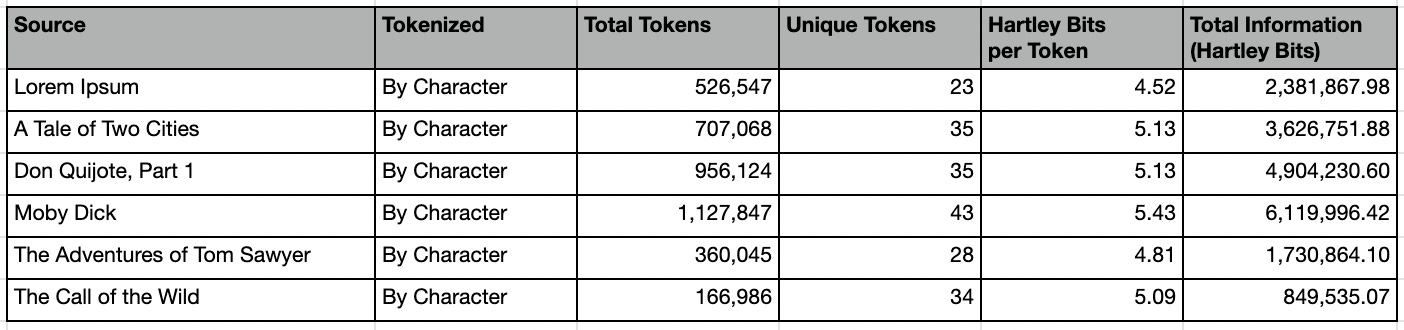

When it comes to tokenization we have two obvious choices: by character (e.g. “t”, “h”, “e”), or by word (e.g. “the”). According to works cited, our “Universal Intelligence Test” should work with either, so we tried both.

Below we have included tables with summary statistics for both methods. Along with basic counts, we have also included Hartley Bits (a.k.a zero-order entropy) as a measure of how much information each token and corpus contains.

That said, please note:

information != intelligence

Information, as defined by Hartley, is not the same as intelligence, as defined by Doyle, Hanser, Jenkins, and McCowan.

Here are the summary stats per-character:

Astute readers may notice that the total number of unique characters does not match the 27 expected of English (a-z plus space). This is due to nuances in the text. For example, Lorem Ipsum lacks the letter “k”. Moby Dick includes the character “£”. Although written in English, The Call of the Wild includes the Spanish letter “ñ”, and A Tale of Two Cities includes the French letter “è”.

According to works cited, our “Universal Intelligence Test” should work regardless of the alphabet or symbols used. Ergo, we have left these nuances on purpose, to better examine how universal our test truly is.

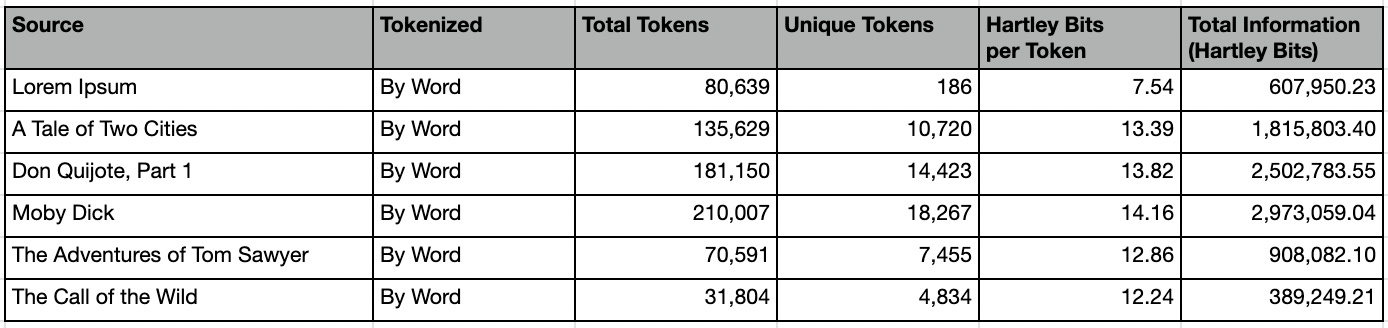

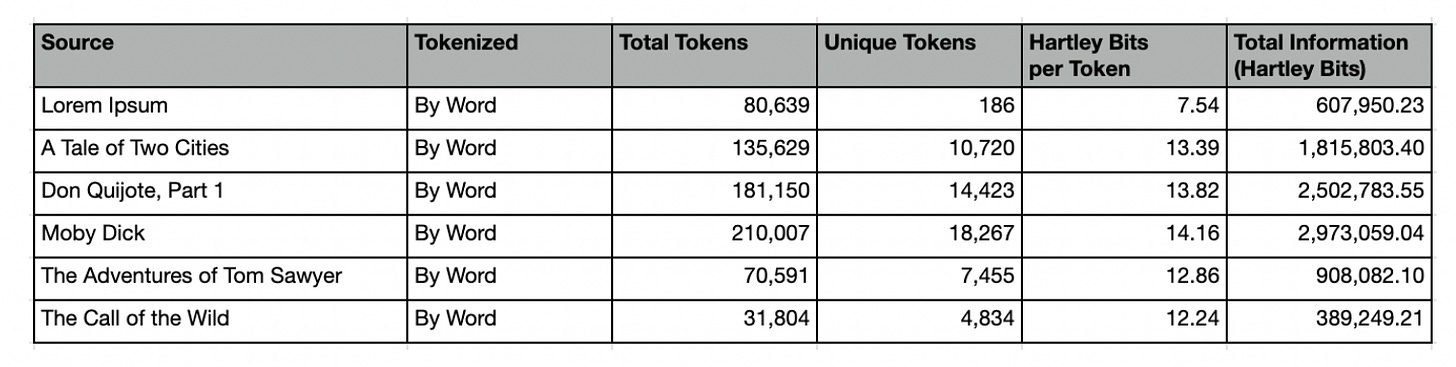

Here are summary stats per-word:

Let’s take a moment to compare the word-based summary statistics of Lorem Ipsum with those of The Call of the Wild.

Despite being roughly 2.5 times longer than The Call of the Wild, our Lorem Ipsum corpus contains only 186 unique words, compared to Wild’s 4,834. If vocabulary is any indication of intelligence, it would seem that Wild is clearly superior. However, as measured by Hartley Bits, we find Ipsum has far more information than Wild.

Can our “Universal Intelligence Test” be used to somehow quantify the difference between information and intelligence? Let’s find out.

Condition #1: the Zipf slope

Recall our first condition for intelligence:

Has a Zipf slope approaching -1

In the first version of this research, we found ≥ 0.19 absolute error for all data when we considered their full distributions. As is often the case, weirdness in the “right tail” (extremely rare tokens) is to blame. Comparing these differences in “Zipfyness” is left as an exercise left to the reader (you can find the data and code used to create this article on github). We have limited our analysis here to the top n tokens.

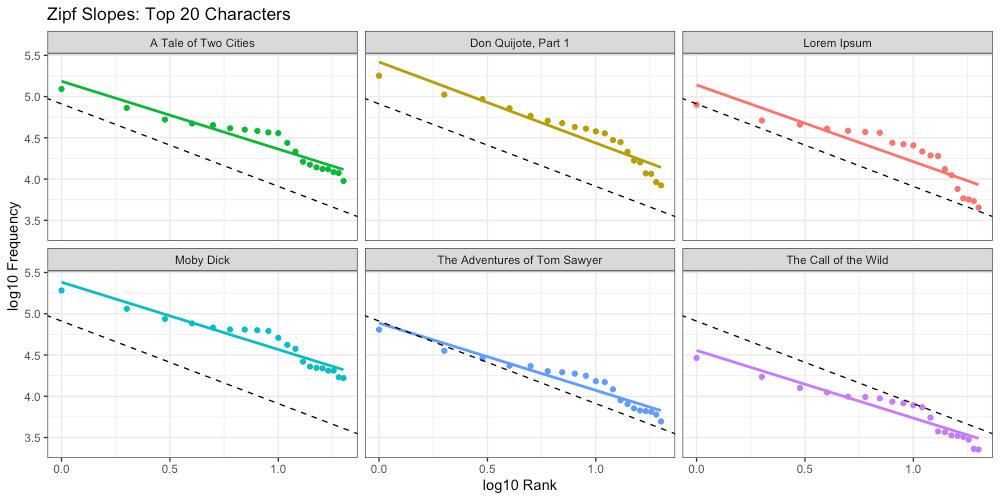

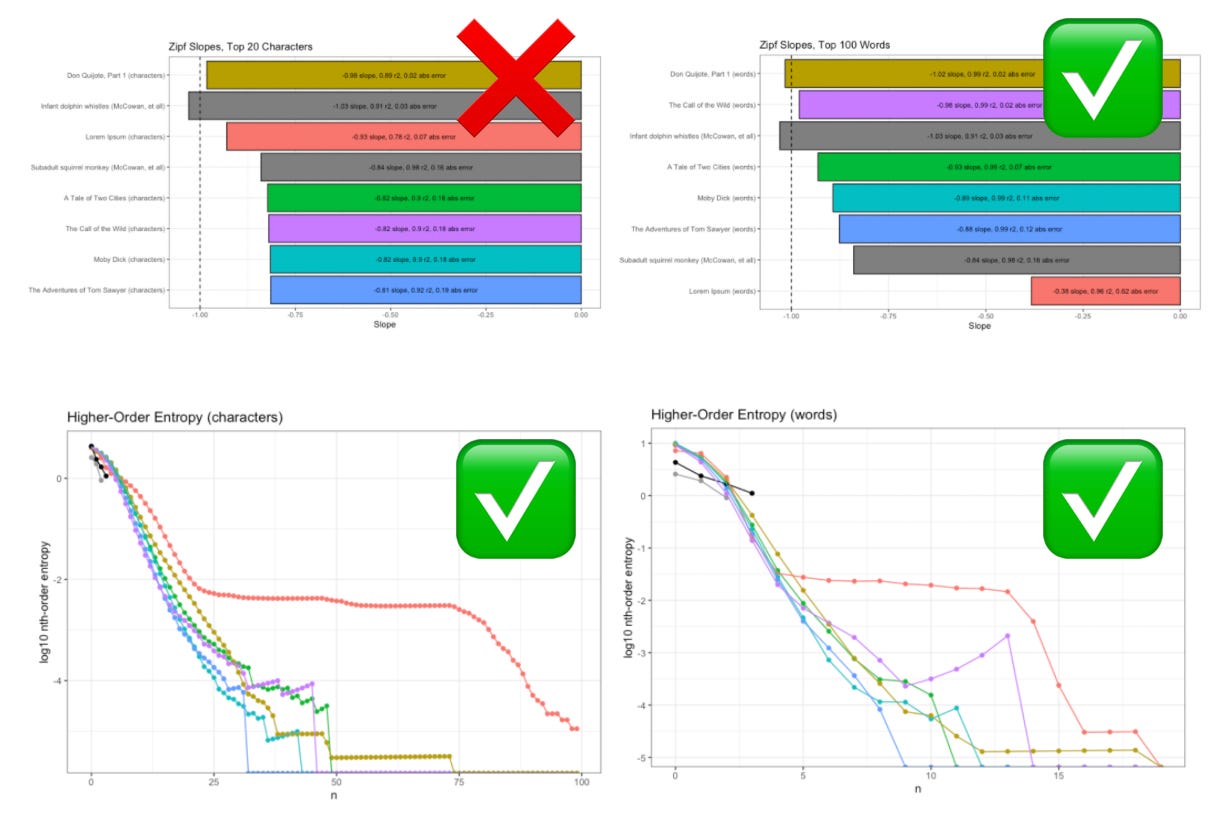

Below we have visualized the distribution of the top 20 characters for each of our sources, along with the Zipf slope (aka linear regression) for each. The dotted black line represents the ideal slope (-1).

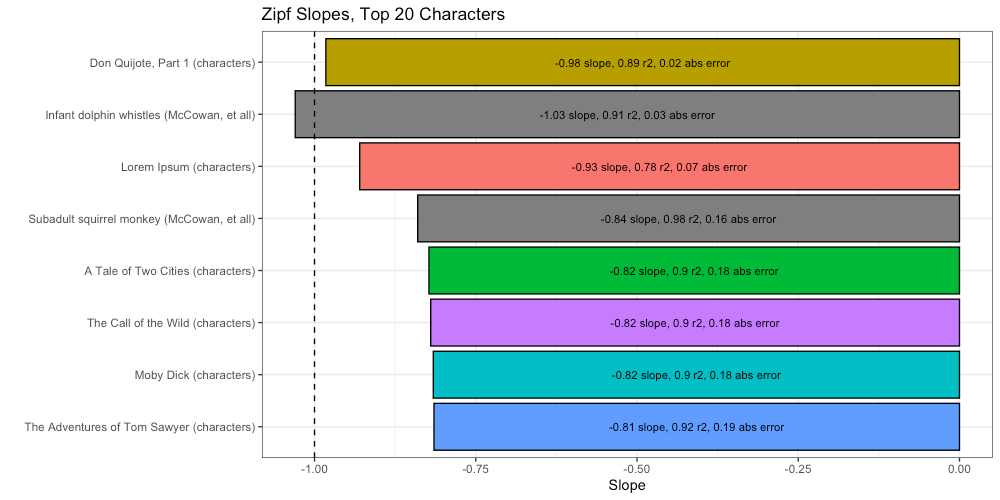

We can compare these Zipf slopes to the ideal (-1) to get a measure of absolute error, and using that, compare our results to those of McCowan, et all:

By this measure we find that Don Quijote is the most “Zipfy”, followed closely by infant dolphin whistles. Oddly, we find Lorem Ipsum beats subadult squirrel monkey chucks, and all of our remaining texts. Unless Lorem Ipsum has more intelligence than Moby Dick, our “Universal Intelligence Test” is off to a rough start.

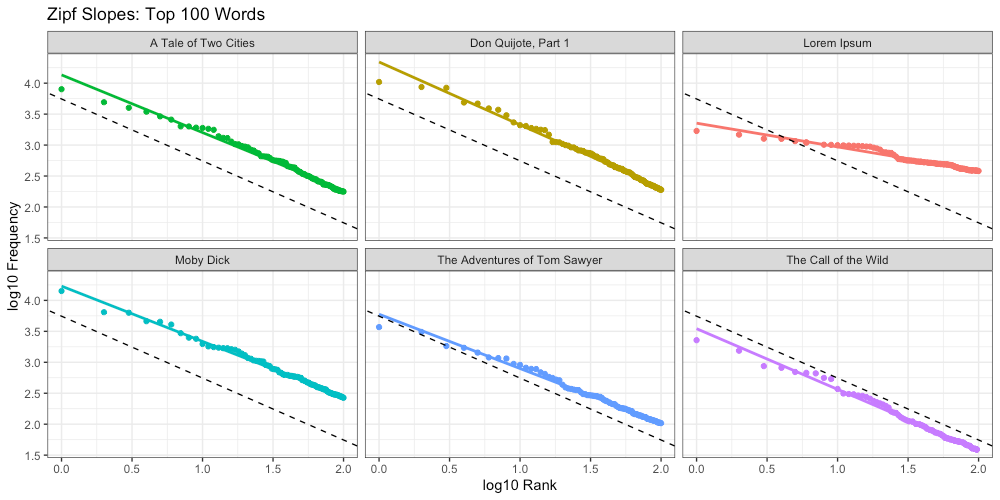

Below we did the same, this time for our top 100 words:

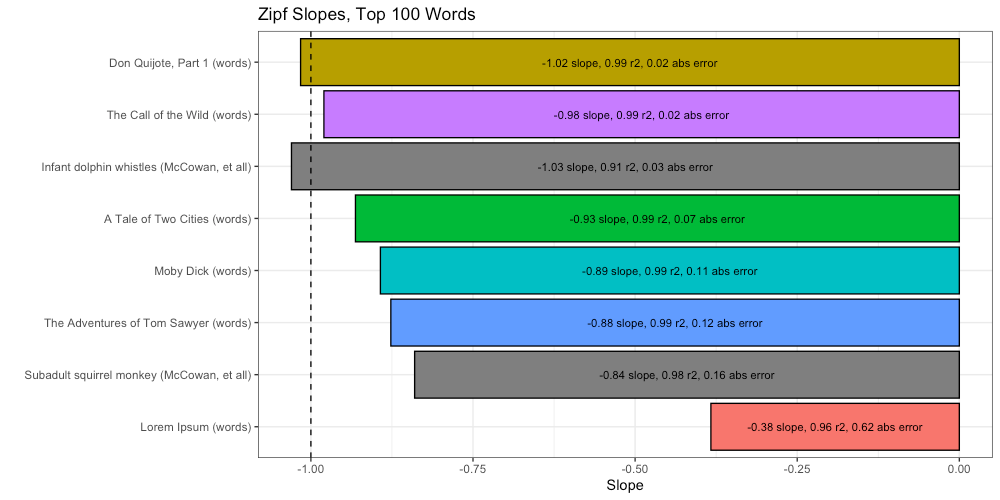

Again we compare these Zipf slopes to the ideal (-1):

The above plot shows us a few interesting things.

First, a glimmer of hope that this “Universal Intelligence Test” could possibly work. Lorem Ipsum is now at the bottom of the list, far removed from the others. This is a promising thing to see.

Second, according to this ranking, baby dolphins remain more intelligent than 3 out of our 5 texts. Although this is certainly possible (especially if Douglas Adams is to be believed), I remain skeptical. We need to go deeper.

Condition #2: higher-order entropy

Recall our second condition for intelligence:

Shows evidence of higher-order entropy

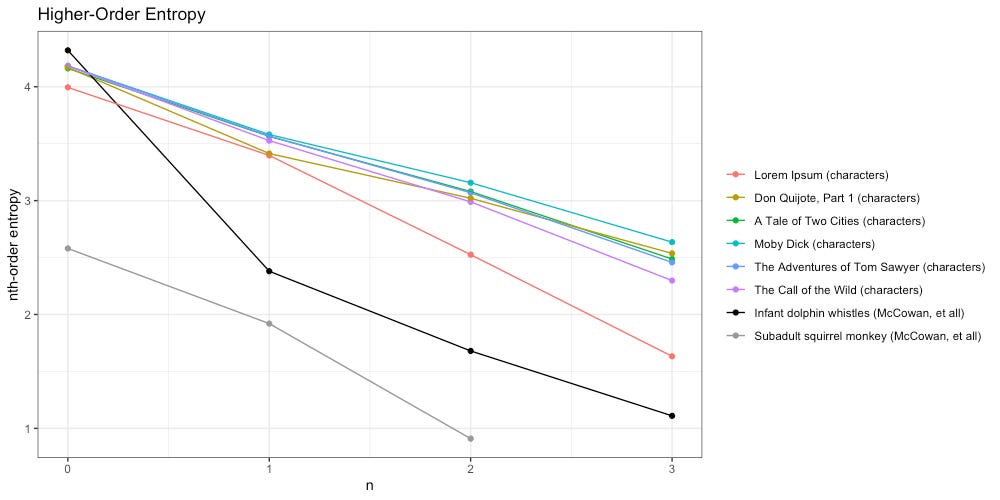

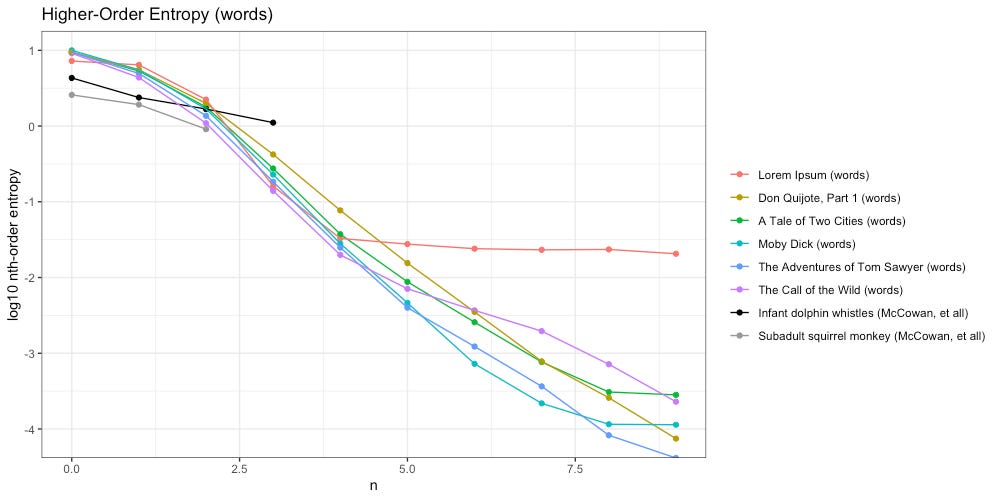

Once again we will start by tokenizing our texts by character. How do they compare to each other, and the work of McCowan, et all?

We see the higher-order entropy of all texts (including Lorem Ipsum) decays slower than both infant dolphin whistles and subadult squirrel monkeys. Unfortunately McCowan, et all, do not provide any data beyond third-order entropy.

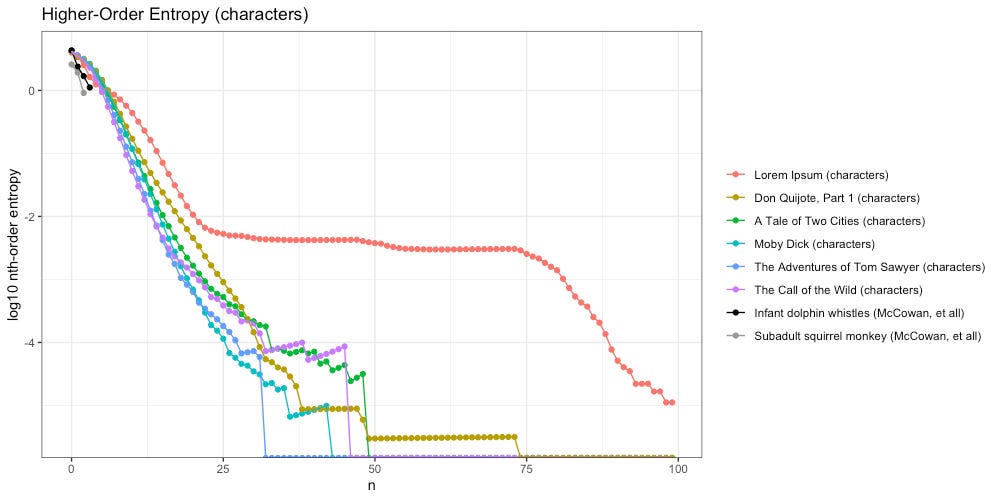

We extended our analysis to hundredth-order entropy. We restrict our ngrams to the lines of the original text transcription. Below are the results, with the y-axis log base-10 transformed for scale:

When looking at Zipf slopes of characters, we were unable to distinguish Lorem Ipsum from the rest of our texts (those that contain intelligent communication). In the plot above, the difference couldn’t be more obvious. Unlike the rest of our texts, Lorem Ipsum quickly flattens out, and stays flat, through the 75th-order; another clue towards a “Universal Intelligence Test” that might actually work.

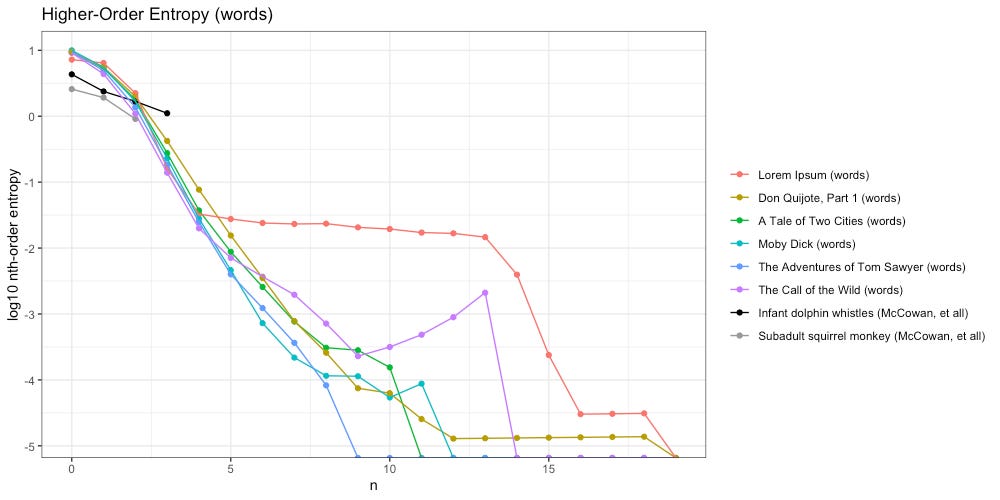

Below we have done the same, tokenized by words:

By the time we reach 20th-order, all entropy has decayed to zero. Once again we see Lorem Ipsum is the odd man out. But what is going on with Call of the Wild here? Why does higher-order entropy spike from 9th through 13th-order?

This passage can help illustrate (from Chapter VI: For the Love of a Man):

“Pooh! pooh!” said John Thornton; “Buck can start a thousand pounds.”

“And break it out? and walk off with it for a hundred yards?” demanded Matthewson, a Bonanza King, he of the seven hundred vaunt.

“And break it out, and walk off with it for a hundred yards,” John Thornton said coolly.

In our word-based tokenization we ignored all punctuation, and converted everything to lowercase, as is standard practice. Here this resulted in two nearly-identical sentences (here is what the computer sees):

and break it out and walk off with it for a hundred yards demanded matthewson a bonanza king he of the seven hundred vaunt

and break it out and walk off with it for a hundred yards john thornton said coolly

Once we reach the 5-gram “and break it out and”, the next word is always “walk”, which is always followed by “off”, etc. In this example, entropy disappears for awhile. But once we reach that 13th token- bam- uncertainty returns.

The result is 13th-order entropy, since the 13-gram “and break it out and walk off with it for a hundred yards” might be followed by the word “demanded” or “john”. The log10 scale used in the above plot magnifies this uncertainty.

Questions, Answers, and Speculation

Does our “Universal Intelligence Test” actually work?

This is not conclusive by any means, but the initial analysis is promising.

In three out of our four tests Lorem Ipsum was clearly distinct from the other groups. When we look at both conditions together, we do even better.

For example: when looking at The Call of the Wild (purple) in terms of higher-order entropy of words (bottom-right above), it spikes suspicious close to Lorem Ipsum (red). However, if we also consider the differences in Zipf slope (top-right above) the distinction between intelligent and unintelligent is made clear.

I think McCowan, et all, are on to something here.

Can we find a counter example?

Can we find something that passes the “Universal Intelligence Test” despite objectively lacking intelligence? Can we find an example of unintelligent text that shows a Zipf slope approaching -1 with higher-order entropy that doesn’t look like the Lorem Ipsum example above?

My gut says “yes”.

Can we use this test to compare intelligence?

Note that in the paper for SETI, McCowan, et all, are only considering the question: “Can we detect intelligence?” Attempting to measure that intelligence so that it can be compared is an entirely different, and much tougher, question.

In the body of the article above, we facetiously considered the ranks of Zipf slopes as an analog for ranks of intelligence, which was (a) a joke and (b) never the intent of McCowan, et all. That said, it remains an intriguing question.

How do we rigorously define the second condition of our test?

As we saw, the higher-order entropy of Lorem Ipsum looks kinda weird compared to the intelligent texts. Unfortunately, “kinda weird” is not a very rigorous definition of what we are looking for here. Neither is “shows evidence of higher-order entropy”.

Can we reduce the insights of higher-order entropy to a point estimate?

How can we better define the second condition of our test? This is another tough question, beyond the scope of a single article.

Why does “Lorem Ipsum” flatten out like that?

I assume this is due to long sequences of repeating text, like we saw with Call of the Wild above. It deserves further investigation.

Is there a relationship between vocabulary size, decay of higher-order entropy, and “intelligence”?

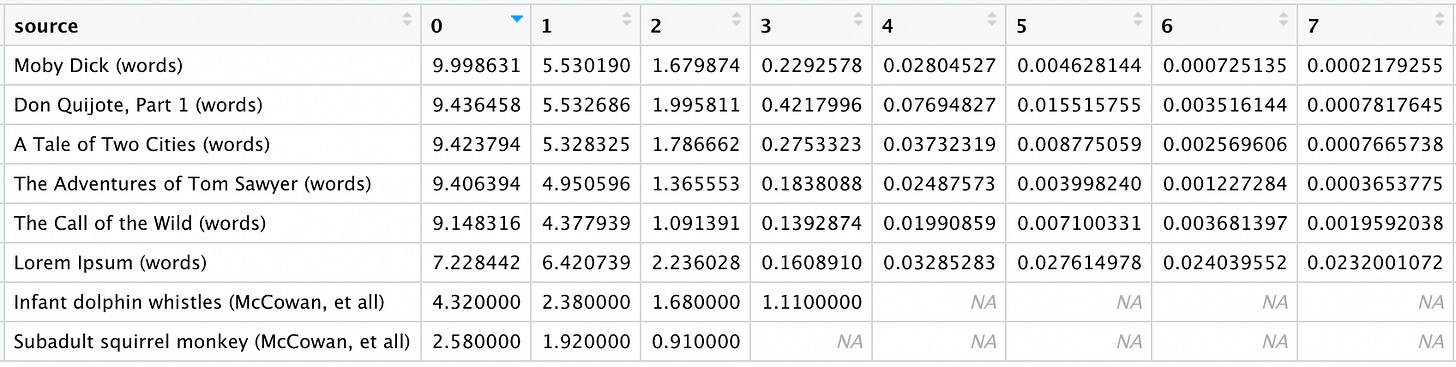

Recall our summary stats:

The Call of the Wild (4,834 unique words) and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (7,455) have much smaller vocabularies than Moby Dick (18,267) and Don Quijote, Part 1 (14,423).

This difference in vocabulary size is reflected in the 0th-order entropy (Shannon’s). Since Moby Dick has the biggest vocabulary (18,267), it faces the most uncertainty when trying to pick a word without context. As we would expect, 0th-order entropy is directly proportional to vocabulary size.

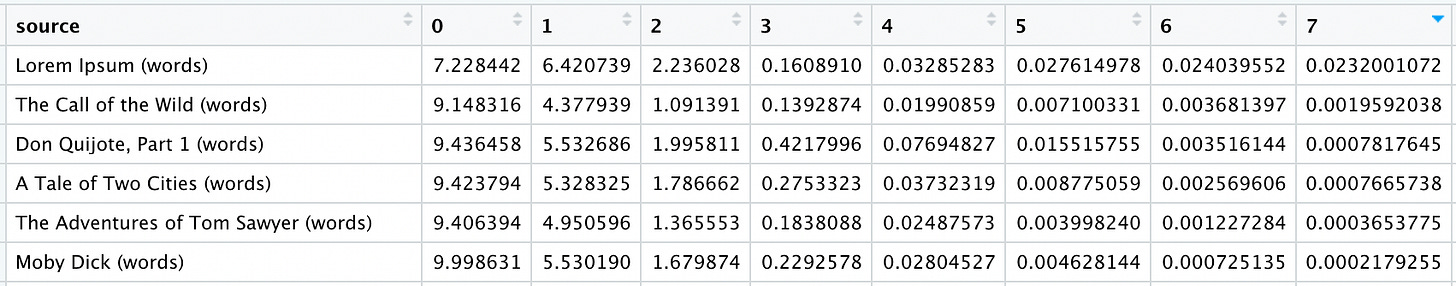

However, by the time we reach 7th-order entropy, the ranks change dramatically:

Now we find Moby Dick (largest vocabulary) at the bottom of the list (lowest entropy, most order), with Wild and Tom Sawyer (the two smallest vocabularies) nowhere near each other. Whatever relationship may or may not exist here is not immediately clear; further analysis is needed.

Are dolphins really more intelligent than Charles Dickens?

Possibly. This much I know for sure: I do not have the data to compare dolphins beyond 3rd-order entropy at this time. I would be fascinated to see what happens if we compared dolphin and Lorem Ipsum at 10th, 50th or 100th-order entropy.

This raises the questions: how complicated is the dolphin language? How large is the average dolphin’s vocabulary? Does dolphinese even include a 10th-order entropy against which to compare?

We must also concede a bit of “apples-to-oranges” here; we are comparing the noises of dolphins to written languages of humans. It would probably make more sense to compare dolphin whistles to phonemes instead.

Where do we go from here?

As usual, this research has left me with more questions than answers. I’m heading back to the lab to test out a few ideas, and will report back once I do.

Stay tuned.

Subscribe on substack so you don’t miss it.

Update- continue reading:

Josh Pause is a cranky old man who isn’t pretty enough for Instagram. You can find him on LinkedIn or Substack instead. The code and data used for this article can be found here. Please get in touch if you find an error, or have an idea for a future collaboration.

Works Cited

Hamptonese and Hidden Markov Models, 2005, Hampton, Le

Information Theory Applied to Animal Communication Systems and Its Possible Application to SETI, 2002, Doyle, Hanser, Jenkins, McCowan

Using information theory to assess the diversity, complexity, and development of communicative repertoires, 2002, Doyle, Hanser, McCowan

Transmission of Information, 1928, Hartley